Lakewood

Community History

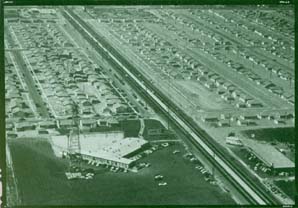

Lakewood is a city ten miles southeast of Los Angeles that in 1950 broke new ground-literally and figuratively-when the Lakewood Park Company started building what would become the nation’s first post-war planned housing development, consisting of 17,500 houses on about 3,500 acres. Lakewood emerged from a former sugar beet field to become a model planned community, complete with street lighting and underground wires, assembly-line construction of about 50 houses a day, berms between residential streets and the highway, and a car-friendly prototype shopping area called Lakewood Center.

The community’s size also eclipsed that of many long-established cities such as Holyoke, Massachusetts, and Santa Ana, California. Promoted with slogans such as “Lakewood – My Home Town” and “Lakewood, Tomorrow’s City Today,” the community was built just in time for war veterans and their families to buy their first homes with the help of the G.I. Bill of Rights, which let buyers put little or no money down and pay for their mortgages with low-interest 30-year loans.

As the unincorporated Lakewood grew from a small village in 1950 to a community of more than 70,000 residents in less than three years, so grew its municipal needs. Lakewood thus had three choices: become annexed to nearby Long Beach, remain unincorporated and continue to receive county services, or incorporate as a city. In 1954, residents chose the latter option and voted to incorporate as a city, the largest community in the country ever to do so and the first city in Los Angeles County to incorporate since 1939.

However, the incorporation had a twist: while the new City Council would set policy and budgets at the local level, members would continue to contract with Los Angeles County to receive a wide range of county services such as road repair, water and sewer services, and fire protection. This novel arrangement-which let the city retain local control of its government while tapping efficiently into existing services-was spelled out in a document called the Lakewood Plan, that was adopted and modified by many other communities in California and the United States that wanted to incorporate as well.

Today Lakewood-with 26,000 housing units, most of them single-family detached homes-remains known for its community services and quality of life as a bedroom community. The community is studied by historians and city planners because of its distinction as a ground-breaking type of suburb and because of the Lakewood Plan’s visionary combination of local and county services. Among other things, Lakewood introduced a number of innovations into suburban development-such as assembly-line house construction-and is often compared to Levittown, New York.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

Lakewood was a massive housing development consisting of 17,500 single-family homes built in the early 1950s ten miles southeast of Los Angeles. When built it was the largest-ever private land development in the United States, conceived of and built by the Lakewood Park Company’s creative triumvirate of Louis Boyar, who had been planning his “dream city” since the late 1930s; Mark Taper, the master builder who coupled mass-production construction with quality housing materials; and Ben Weingart, the brains behind the prototype Lakewood Center shopping complex that anchored Lakewood’s tax base.

The timing for the development of Lakewood was perfect, as a real estate boom in the Los Angeles region dovetailed with the G.I. Bill of Rights, which provided returning World War II veterans with low-interest mortgage loans insured by the government and requiring little, if any, money down.

Housing in Los Angeles County had been so scarce for these veterans and their new brides and young families that when the Lakewood Park Company opened its sales office on April 2, 1950, more than 10,000 people arrived to sign up for houses before they had even been built. The two- and three-bedroom homes, all built to Veterans Administration specifications, catered to young families. They were also built in an assembly-line fashion that minimized wasted time and materials: excavators dug a foundation in fifteen minutes; individual specialized teams built floors, walls, and roofs; and developers kept the landscaping simple if spartan, planting a single tree in front of each house.

Originally, the area was inhabited by Gabrielino Indians, hunter-gatherers who were the first to greet Spanish explorers, starting with the 1769 arrival of Gaspar de Portola. In 1784, the area became a cattle ranch land grant for Manuel Nieto, whose claim was split into six great ranchos, including the Rancho Los Alamitos, located at what today is the center of Lakewood. Over the next century Rancho Los Alamitos changed hands several times.

In 1881, developers purchased the rancho and the following year changed its name to the Bixby Investment Company, though they leased the property for sheep grazing. Around 1900, Montana Senator William Clark of Montana and his brother bought 8,139 acres of what had been Rancho Los Alamitos for about $400,000. They called their holdings the Montana Land Company and grew sugar beets.

The genesis of today’s development occurred in 1930 after Clark descendent and now-landowner Clark Joaquin Bonner bestowed the name Lakewood on an upscale country club he was building around Bouton Lake (formed from artesian well drilling in 1895). Though the Lakewood Country Club opened in 1933, the Depression-era economy prevented financial success and forced Bonner to prepare the alternate development plan of Lakewood Village, a modest middle-class development. Various neighborhoods emerged between then and the late 1940s, including the Mayfair section and Lakewood Gardens, but Bonner died in 1947 before he could set in motion his plans to build thousands of new homes. Just two years later, the trio of Weingart, Boyar, and Taper formed the Lakewood Park Company and bought Bonner’s remaining 3,500 acres from his widow for $8 million. They publicized their plans to build “Lakewood, Tomorrow’s City Today,” and started construction the following year.

In 1951, the city of Long Beach – which had long had its eye on Lakewood to expand its own territory – publicized a report recommending that Lakewood be annexed to Long Beach. This and other efforts by Long Beach to annex Lakewood’s property prompted the Lakewood Taxpayers’ Association and other motivated groups to lobby to incorporate the community as a city. In May 1953, a group of civic-minded citizens filed “Articles of Incorporation of the Lakewood Civic Council Inc.” with the Secretary of State, and following a year of legal and financial battles, residents voted on March 9, 1954, to incorporate as a city.

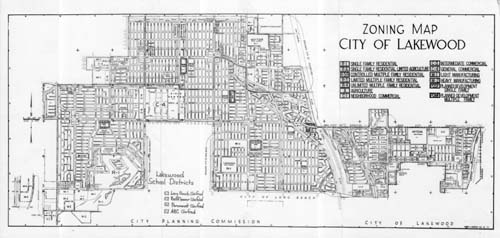

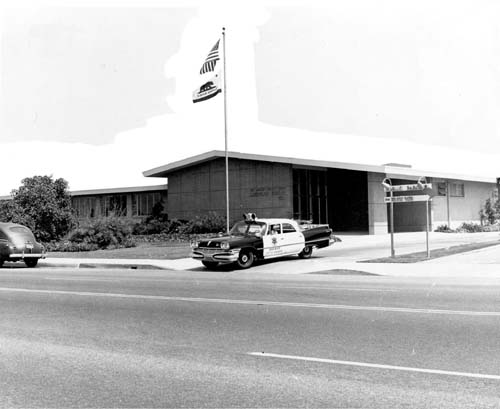

With its seven square miles, 105 miles of paved and lighted streets, assessed worth of $34.5 million, and more than 70,000 residents, Lakewood – the state’s 16th-largest city-also became the largest community in the United States ever to incorporate. As part of Lakewood’s new municipal status as a city, which became official on April 16, it operated in accordance with the Lakewood Plan, an agreement between the city and Los Angeles County in which the county would provide Lakewood with the same services it provided to unincorporated areas in the county. Lakewood therefore tapped into existing county services such as road maintenance, health department, building inspection, sewer, library, and fire district. It contracted with the sheriff’s department for police protection.

The enthusiasm residents brought to civic pride was evident on the night of the first city council meeting on April 16, 1954, when councilors met from 8 p.m. to 5:30 a.m. reviewing and discussing ordinances and issues that had been brewing during the community’s early unincorporated years. The new experiment was not easy to carry out-the first five City Council members were political novices in charge of the largest community in the United States to incorporate at once, and started with scant municipal funding and the enormous task of finding schooling for the community’s thousands of school-aged children-but officials have proven since 1954 that the experiment was a success.

The city of Lakewood took its name from the Lakewood Country Club conceived of in 1930 by developer Clark Joaquin Bonner, who inherited the Montana Land Company from William and Ross Clark. Bonner named the country club by melding the image of Bouton Lake-a body of water formed from artesian well drilling in 1895-with the trees surrounding the lake. When the Lakewood Country Club opened in 1933, during the Depression, it was a financial failure, so Bonner started a modest development called Lakewood Village. The development grew slowly and Bonner died in 1947 before he could play out his plan to build thousands of houses. It was only after the Lakewood Park Company was formed in 1949 by Louis Boyar and two associates that Bonner’s remaining property – along with the country club – would be developed as a major planned community dubbed the “City New as Tomorrow.”

The Lakewood Plan was the “instruction manual” for incorporation that a group of residents devised during the early 1950s in response to a series of annexation battles with southern neighbor Long Beach. The plan laid out a county contract form of government by explaining the agreement that the city of Lakewood had with the County of Los Angeles; as such, it became a template for other municipalities considering incorporating or wanting to find ways to solve complicated municipal problems and to use government services efficiently. As Lakewood was growing from a small sleepy village in 1950 to a 17,500-house planned development by 1953, Long Beach undertook a series of fights-some successful-to annex Lakewood.

In response, Lakewood citizens formed the Lakewood Committee for Incorporation, seeking to incorporate about seven square miles of property, including some 70,000 residents, 105 miles of paved and lighted streets, and the Lakewood Center shopping center. As part of the campaign the committee crafted the Lakewood Plan, which specified which municipal duties would be handled by the community and the county, respectively. According to this county contract form of government, the Lakewood City Council would pass laws, set policy, make a budget, and do community planning. However, it would also tap into existing county services by contracting for street construction and repair, animal pound regulation, health laws, building inspections, tax collection, library and school services, and fire and police protection. The Lakewood Plan was an exceptional document because it spelled out clearly the dual system of Lakewood’s municipal management, showing how Los Angeles County handled most services while the city kept control of local affairs. The contract system of government was an experiment that was carefully watched and later emulated by other communities.

Angelo M. Iacoboni, the first mayor of Lakewood, was chosen to lead the first City Council after the community voted to incorporate as a city in 1954. In the early 1950s, Iacoboni, a local attorney, joined an alliance of residents who were opposed to having Lakewood annexed by Long Beach and who promoted incorporation. At one point during the fight, Iacoboni served as a trial lawyer for pro-incorporation residents as he presented evidence in court. Pictures of Angelo M. Iacoboni are in the library lobby and a bust is in the library foyer.

In 1947, residents Jess Solter and former Bolivian Consul Walter Montano began the Lakewood Pan American Fiesta as a way to improve and strengthen relations among Pan American countries. At their request, the Lakewood Lions Club adopted the idea as a community project, that would include a flag exchange, the naming of a park for the event, and an annual parade. Held each April, the week-long festival became the country’s biggest program for promoting good relations among Pan American countries and included a banquet and ball in addition to the sports festival and other activities. It grew to become a non-profit organization called the Lakewood Pan American Festival, Inc., and aspects of the festival can be seen in Lakewood with the naming of three parks after Latin American heroes Simon Bolivar, Jose San Martin, and Jose del Valle.

George Nye Jr. was one of Lakewood’s first five city councilors following the community’s incorporation in April 1954, and was an early Lakewood mayor. A major advocate of the incorporation movement, he was also an artist and teacher who designed the seal for the newly incorporated city. The seal showed Douglas MacArthur School, St. Pancratius Church, a young boy playing ball, and his own home, all superimposed on the original boundaries of Lakewood. The city seal was at the time the only square one in the United States.

Native Americans who lived in the Los Angeles area spoke a language distinct from their neighbors to the North and South of them. They have come to be known as Gabrielino, because many of those who survived European diseases and the disruption of their normal trade patterns and culture went to the Mission San Gabriel in Los Angeles, some voluntarily, others only when confronted by force.

When the Europeans arrived, they discovered many Indian villages between the Pacific Ocean and the San Gabriel mountains. The Gabrielino lived in domed, circular structures with thatched exteriors. Both men and women wore their hair long and used a vegetable charcoal dye and thorns of flint slivers to tattoo their bodies. They required very few clothes, though women usually donned deerskin or bark aprons, and all might wear animal skin capes in cold or wet weather. Those who lived near the coast ate fish and other seafood, in addition to acorns, seeds, roots, and small game animals.

Passing through during the mid 1700s as part of Spaniard Gaspar de Portola’s famous expedition from San Diego to Monterey, Padre Juan Crespi observed that the Indians in the area were very friendly. Nevertheless, during the late 1700s and early 1800s, after dominating the Los Angeles area for hundreds of years, those Gabrielino who did not flee were gradually moved to Spanish missions. Many became laborers for local landowners. Most eventually adopted a more European lifestyle.

In the Lakewood area, Gabrielinos established small villages while continuing to migrate to take advantage of seasonal resources. They lived by hunting and fishing rather than by agriculture, though once European settlers arrived in the late 1700s they were soon put to work on Rancho San Pedro and the San Gabriel Mission and helped bolster the economic success of the mission. In what is now Lakewood, the Indians lived on the plains, which were mostly semi-arid but during heavy rainy seasons got so much rain that the rivers overflowed their banks, creating marshy areas. By the nineteenth century their numbers decreased rapidly due to diseases such as smallpox for which they had no immunity.

Lakewood was first populated by Gabrielino Indians who were hunters and gatherers but did not become involved in agricultural pursuits. That changed after Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portola arrived in 1769, followed shortly after by missionaries and ranchers who put the Gabrielinos to work on ranch and mission projects. In the 1780s, Manuel R. Nieto received a land grant to graze cattle. His descendants later divided the Nieto claim into six great ranchos, including the Rancho Los Alamitos, which means “little cottonwoods” and which is the site of Lakewood Center today.

The property went through a succession of owners in the 1800s and around 1880 was renamed the Bixby Investment Company, though the land retained its ranching purpose through the 19th century. In 1904 the Montana Land Company bought a large parcel of the property, which it leased out for farming and grazing purposes. The site’s ranching heritage was eclipsed by development starting in 1930, with the building of the Lakewood Country Club and small housing developments, and in 1950 with the building of the 17,500-house Lakewood development.

Lakewood has been mostly a bedroom community to nearby industries that include Douglas Aircraft, North American Aviation, Long Beach Naval Shipyards, and Aerojet General, as well as other regional manufacturing plants. It has attracted some companies who do research and development, including the Purex Corporation, which is located in Lakewood Center.