Antelope Valley

Community History

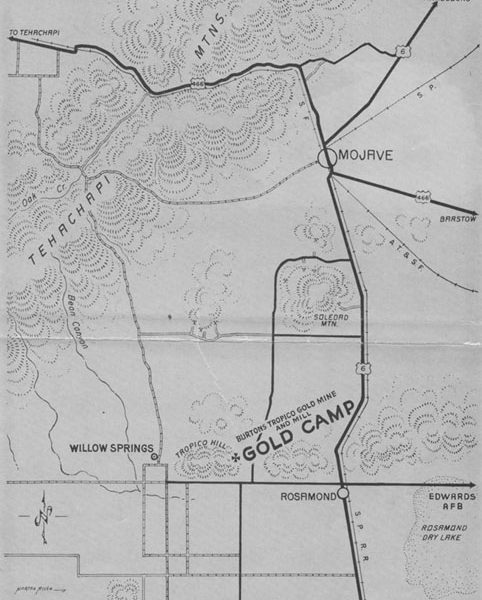

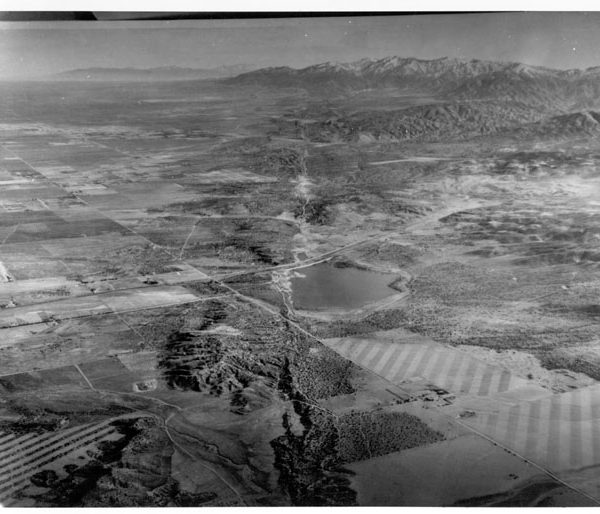

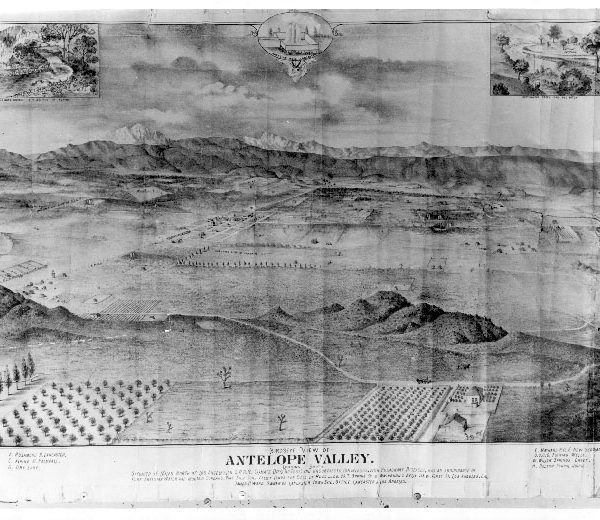

The Antelope Valley is a 3,000-square-mile high desert closed basin that straddles northern Los Angeles County and southern Kern County. One of nine California valleys with the same name, this one lies in the western Mojave high desert and includes the communities of Lancaster, Palmdale, Rosamond and Mojave. Populated by different cultures for an estimated 11,000 years, the Antelope Valley was a trade route for Native Americans traveling from Arizona and New Mexico to California’s coast. Though the first wave of non-native exploration took place in the early 1770s, a later exploratory period starting in the 1840s led to the valley’s first permanent settlement during the following decade, fueled by California’s Gold Rush and new status as American territory. The 1854 establishment of the Fort Tejon military post near Castaic Lake and Grapevine Canyon created a gateway for valley traffic.

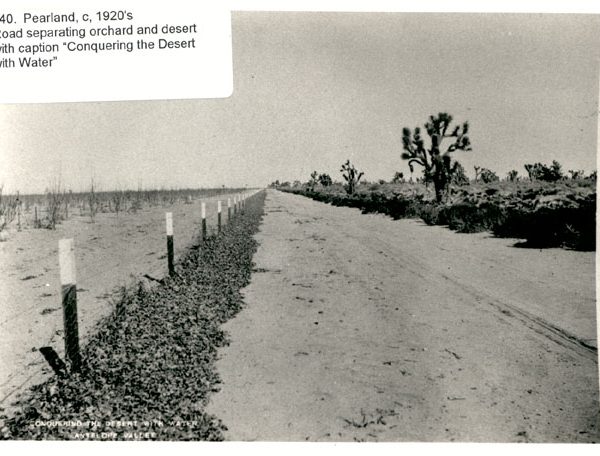

Several developments were integral to the valley’s growth starting in the mid-1800s, including gold mining in the Kerns and Owens rivers; cattle ranching; the start of a Butterfield stagecoach route in 1858; construction of the Los Angeles-to-San Francisco telegraph line in 1860; completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad line in 1876; and ample rainfall during the 1880s and early 1890s, which attracted many farmers. The decade-long drought that began in 1894-the worst in southern California’s recorded history-decimated the regional economy and forced many settlers to abandon their homesteads, but after the turn of the twentieth century irrigation methods and electricity brought back local farming. The 1913 completion of the aqueduct spanning 233 miles between the Owens Valley and Los Angeles also revived the valley’s economy. Today the Antelope Valley retains elements of its agricultural past but its economic base is now supported by aerospace and defense industries.

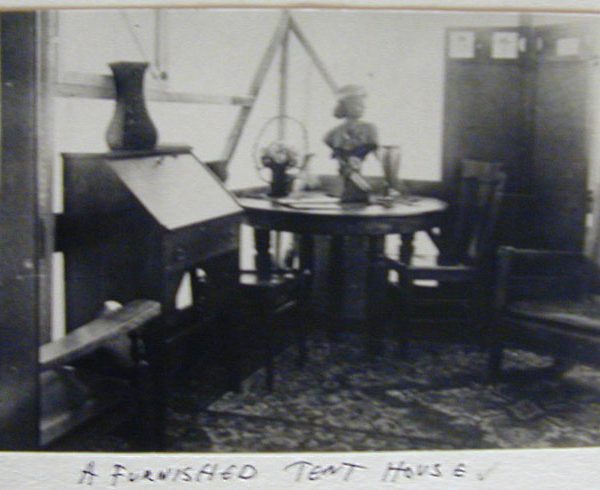

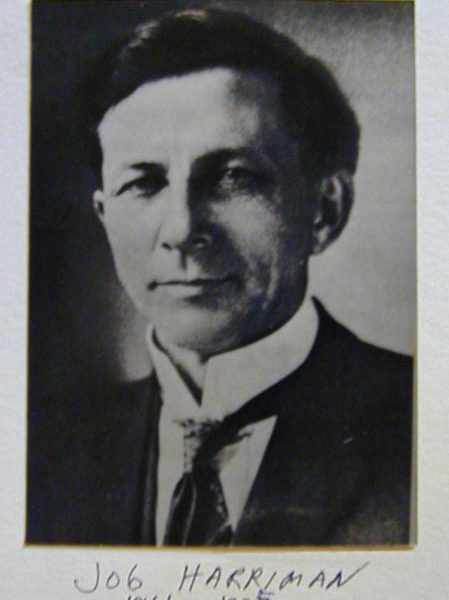

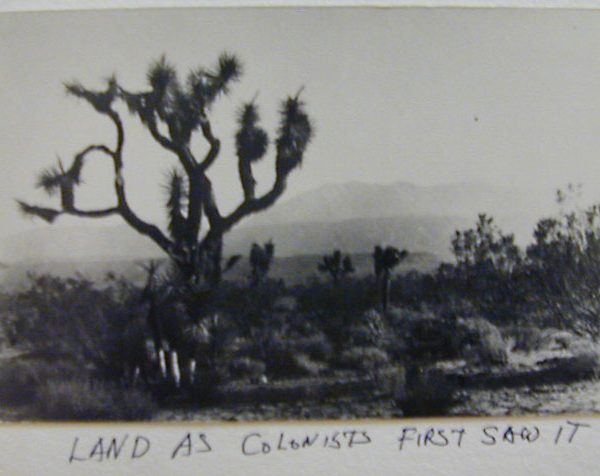

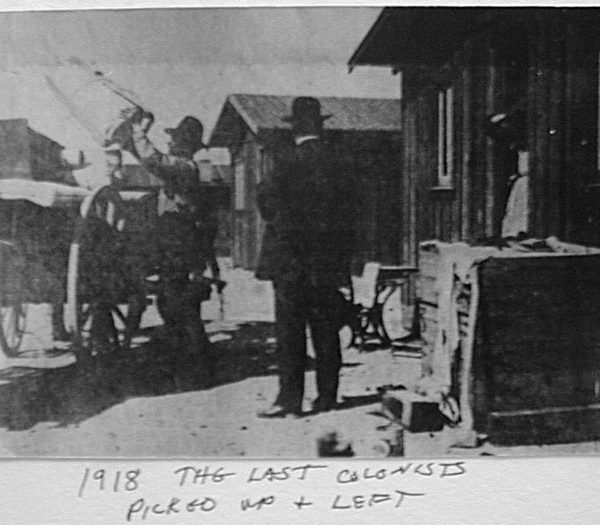

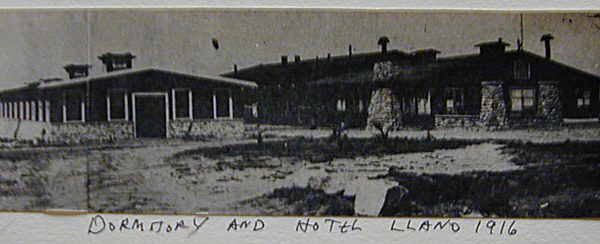

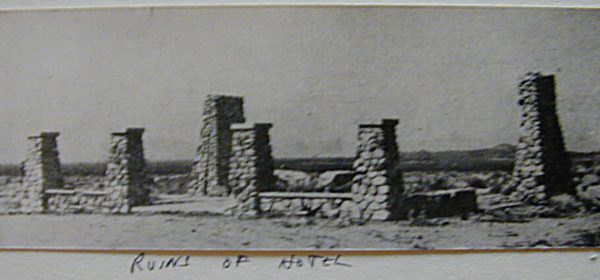

On May 1, 1914, the Llano del Rio Colony, a socialist utopian community, was established north of Los Angeles in the southeast Antelope Valley. Among its founders was Indiana native Job Harriman, an idealistic and charismatic young lawyer who had unsuccessfully run on the first-ever Socialist Party platforms for Vice President in 1900 and mayor of Los Angeles in 1911. Thwarted by political efforts to effect social change, Harriman and his fellow visionaries instead thought they could accomplish their utopian goals via the colony’s cooperative economic system. Llano del Rio was promoted nationally by the socialist magazine The Western Comrade, and the cooperative thrived for several years-its population exceeding 1,000 people in 1916-until its long-term water supply was diverted by an earthquake fault.

In 1917 about 200 participants moved the colony to Stables, Louisiana, a defunct lumber town, and renamed it New Llano. Despite numerous internal hurdles and external criticism, the colony for more than two decades made its mark as a social experiment. It had one of the country’s first Montessori schools; it was renowned for the production and sale of high-quality food and other items; it was where the national socialist paper The American Vanguard moved its headquarters; it hosted a fertile intellectual and cultural climate, replete with orchestras and theater groups; it set up satellite colonies in Gila, New Mexico, and Fremont, Texas; and its innovative social services-including low-cost housing, Social Security, minimum-wage pay, and universal health care-were decades ahead of their time. Though financial woes and infighting forced the colony into bankruptcy in 1939, Llano del Rio is today considered Western American history’s most important non-religious utopian community.

Shea’s Castle is an architectural curiosity in the southwest Antelope Valley designed to look like an Irish castle. Real estate baron Richard Peter Shea (usually identified as John Shea) built Shea’s Castle as a residence in 1924. The Shea property, which also includes a Kitanemuk petroglyph site and a private airstrip, passed through many hands and is still privately owned today.

The Overland Mail Stage line, commonly called the Butterfield Stage line after its organizer John Butterfield, ran up San Francisquito Canyon, by Elizabeth Lake, along the southwest edge of Antelope Valley, and though Tejon Pass. Although there are no stage stations in the Antelope Valley, almost any old building in our area might be touted as a Butterfield Stage station, even though miles from the actual route. Later stage lines, including local short lines, have been confused with the Butterfield which operated from 1858 to 1861.

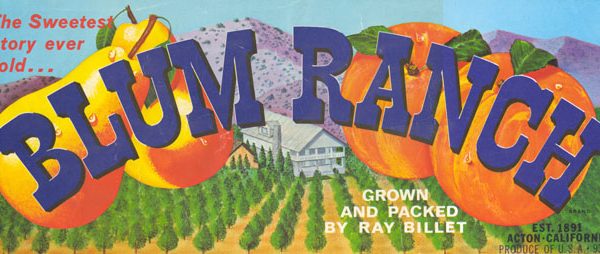

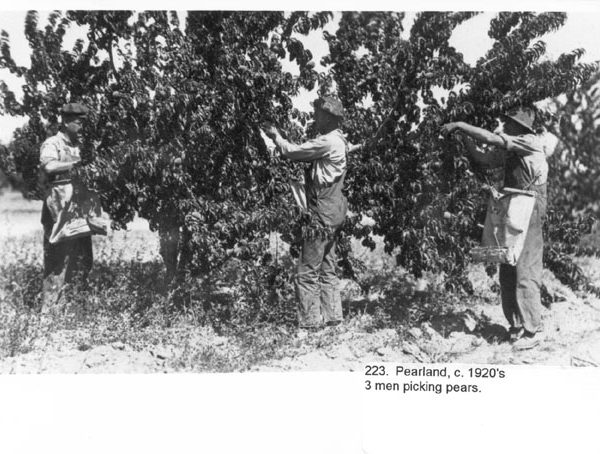

Founded in 1893, Littlerock is an agricultural town with approximately 12,600 residents, located in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains about 50 miles north of Los Angeles. Known today for its orchards, fruit stands, and antique stores, and dubbed “The Fruit Basket of the Antelope Valley,” Littlerock is the Valley’s largest unincorporated community. The area’s original inhabitants were groups of Piute Indians until the first non-native settler moved there during the mid-1860s and stayed until he was killed by a grizzly bear in 1886. In the early 1890s the town’s core population began with a group of settlers who planted almond and pear trees, started a blacksmith shop as the first business, and called the community first Alpine Springs Colony and then Tierra Bonita before changing its name to Littlerock in 1893-the same year that the first post office opened.

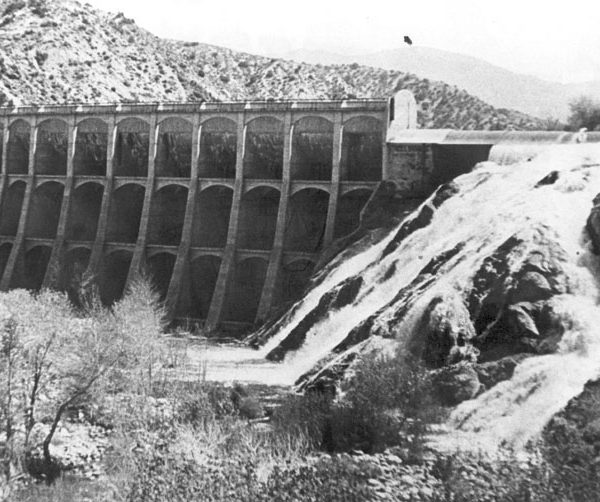

Development milestones continued into the early twentieth century with the 1913 opening of the first schoolhouse and the 1914 founding of the first library. Littlerock Dam-now considered a historical architectural structure-was completed in 1924 to provide water to irrigate the town’s orchards and today also provides recreational amenities such as boating, fishing, and camping.

Edwards Air Force Base began in 1933 as Muroc Air Force Base, a remote bombing range built at Muroc Dry Lake. During World War II, it was a major bomber training base, and in 1947, after taking off from the base, Captain Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in a Bell XI aircraft while flying over Antelope Valley. The base’s name was changed in 1950 to honor Captain Glen W. Edwards, who died while test-piloting the experimental YB-49 aircraft there on June 5, 1948.

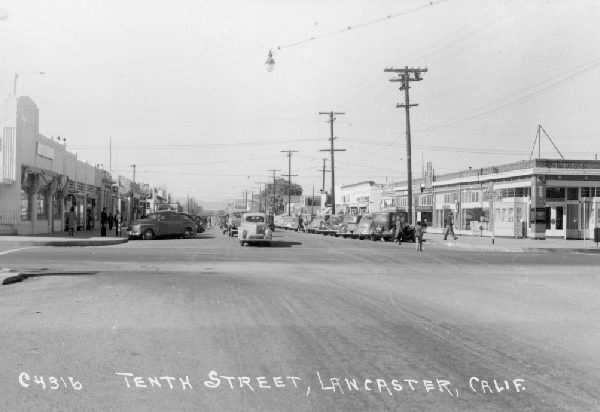

Historic photographs of the Antelope Valley can be found in a number of locations. One major source is the Palmdale City Library:

Palmdale City Library

700 E Palmdale Boulevard

Palmdale, CA 93550

661.267.5600

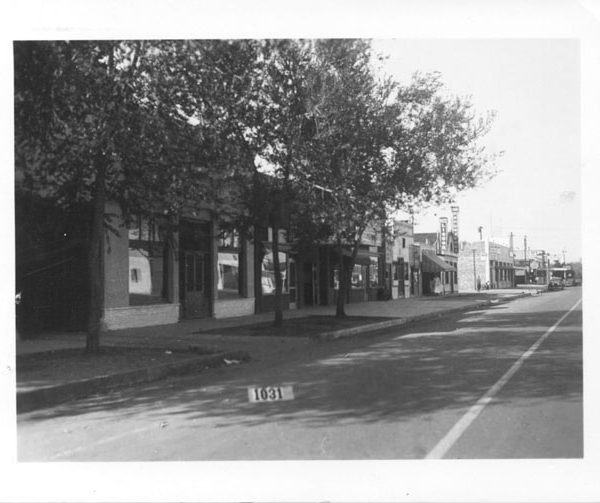

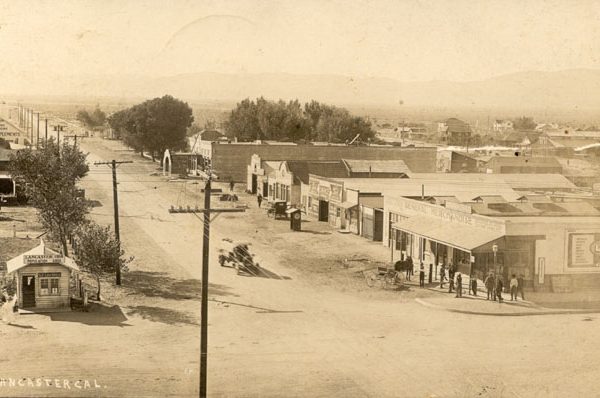

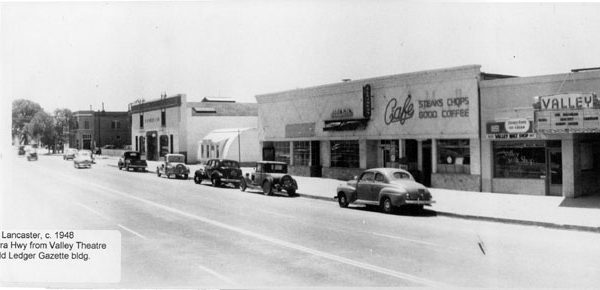

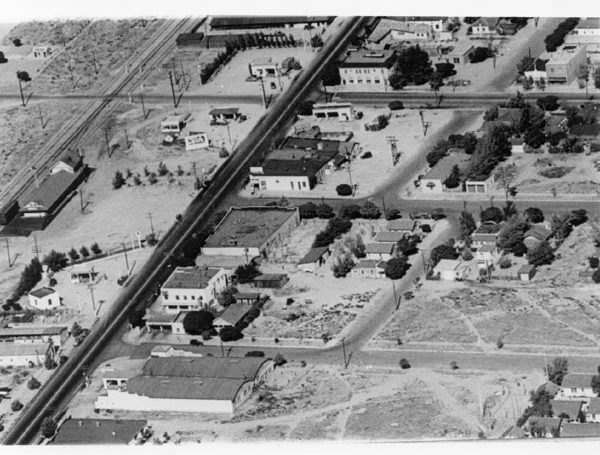

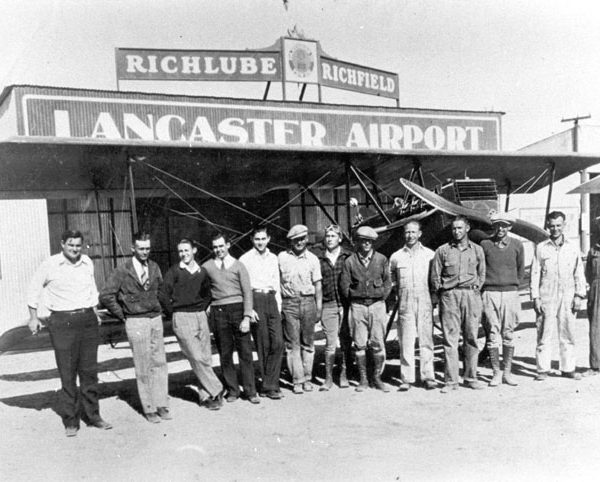

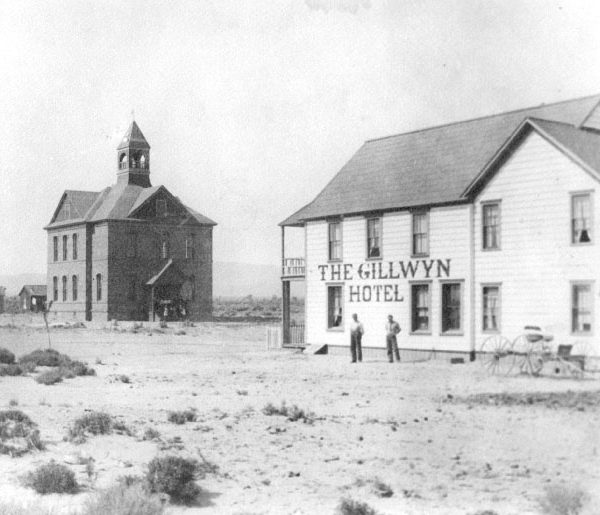

Lancaster – which today calls itself “the heart of the Antelope Valley”-owes its birth to the Southern Pacific Railroad. In the summer of 1876 the railroad laid track through the town’s future location and by September had completed a railroad line through the Antelope Valley, linking San Francisco and Los Angeles. The origin of Lancaster’s name is unclear, attributed variously to the surname of a railroad station clerk, the moniker given by railroad officials, and the former Pennsylvania home of settlers. Train service brought passengers through the whistlestop-turned-community, which with the help of promotional literature quickly attracted new settlers.

The person credited with formally developing the town is Moses Langley Wicks, who in 1884bought property from the railroad for $2.50 per acre, mapped out a town with streets and lots, and by September was advertising 160-acre tracts of land for $6 an acre. The following year, the Lancaster News started publication, making it the first weekly newspaper in the Antelope Valley. By 1890, Lancaster was bustling and booming, and thanks to ample rainfall farmers planted and sold thousands of acres of wheat and barley.

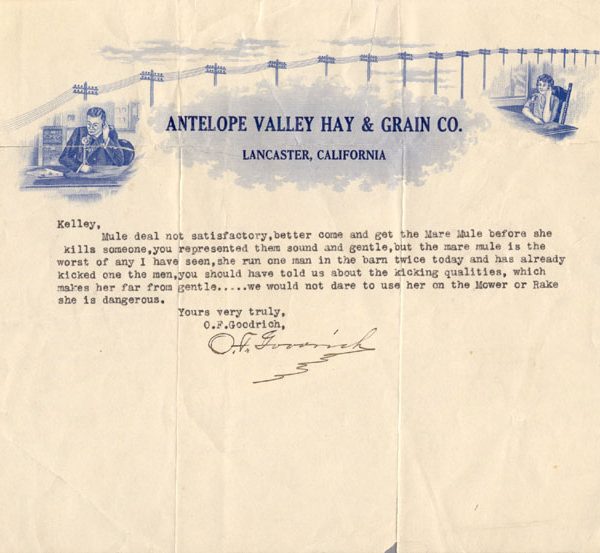

The town was devastated by the decade-long drought that began in 1894, killing businesses and driving cattle north, though fortunes improved somewhat in 1898 following the nearby discoveries of gold and borax, the latter to become a widespread industrial chemical and household cleaner. Thanks to the five-year construction of the 233-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct starting in 1908, Lancaster became a boom town by housing aqueduct workers.

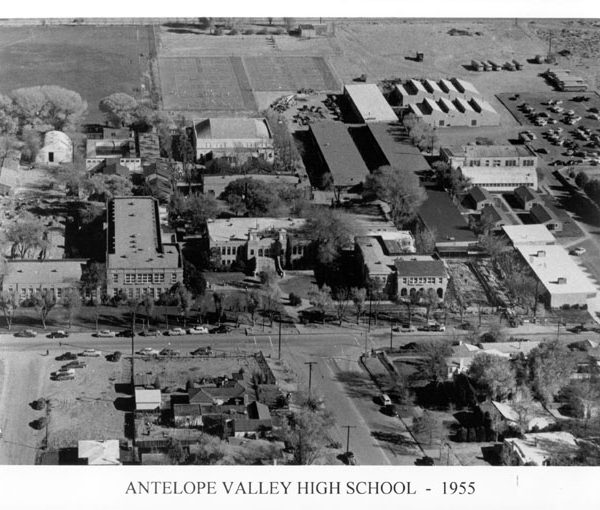

The 1912 completion of Antelope Valley Union High School allowed students from the growing region to study locally instead of moving to distant cities, and the school boasted the state’s first dormitory system to accommodate students from outlying districts. For seven years starting in 1926, a young Judy Garland-then still Frances “Baby” Gumm-lived in Lancaster and honed her skills as a child singer, dancer, and entertainer before going on to become one of Lancaster’s most famous residents. The community began a steady growth spurt in the 1930s, starting with construction of Muroc Air Force Base, frequent flight tests, and later space shuttle landings. Lancaster was controlled politically by Los Angeles County until 1977, when it was incorporated as a city. More information about Lancaster can be found in the following sources:

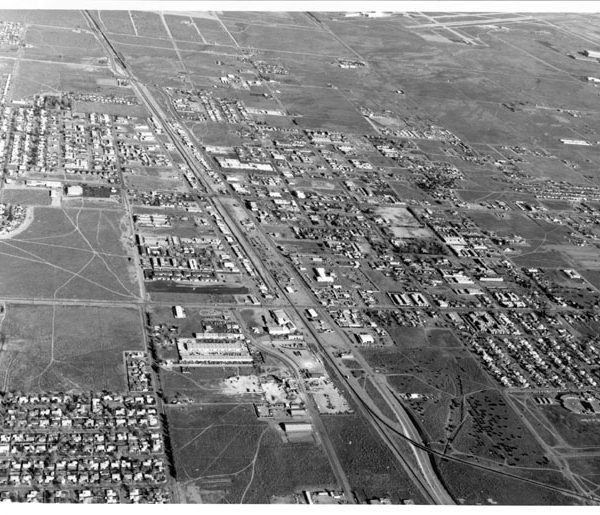

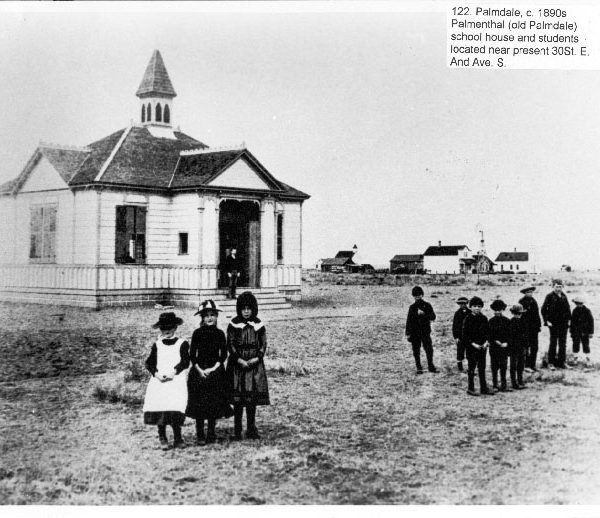

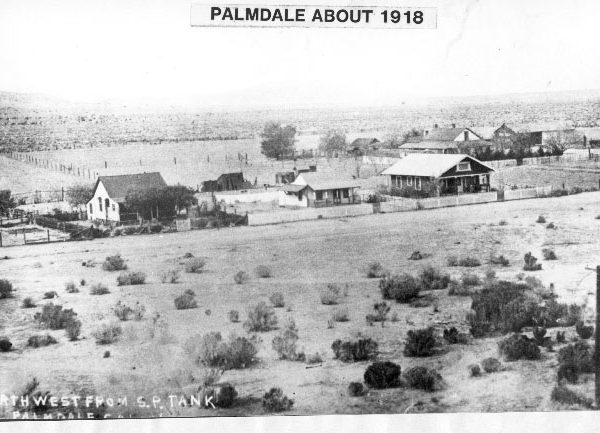

Palmdale, located approximately 60 miles northeast of Los Angeles, is the offspring of long-defunct Antelope Valley communities Palmenthal and Harold. Palmenthal was founded in 1886 by westward Swiss and German settlers who in 1888 named their new community Palmenthal after mistaking the local Joshua trees for palm trees; initially prospering as grain and fruit growers, many settlers abandoned their homesteads after drought decimated their crops and land scams prevented them from clearing their property titles. Harold-also known as Alpine Station and Trejo Post Office-was founded at the junction of the Southern Pacific Railroad and what is now Barrel Springs Road; but it too went under after the railroad moved the site of its booster engine station north of town. Both abandoned communities blended into Palmdale, so-named in 1899, when residents jointly relocated to a new site near the Southern Pacific railroad station and the stagecoach line between San Francisco and New Orleans.

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, irrigation systems and dry farming techniques allowed Palmdale to flourish as an agricultural community known for its alfalfa, apples, and pears. After World War II, Palmdale’s economic base shifted to aerospace and defense industry with construction of Air Force Plant 42 and the Federal Aviation Administration’s Air Route Traffic Control Center. Palmdale became incorporated in 1962 as the Antelope Valley’s first city and in recent decades has experienced astounding growth: its geographic size increased from 2.1 square miles in 1962 to 102 square miles today, and its population soared tenfold from 12,227 residents in 1980 to about 122,400 people today, making it one of the country’s fastest-growing cities. More information about Palmdale can be found in the following sources:

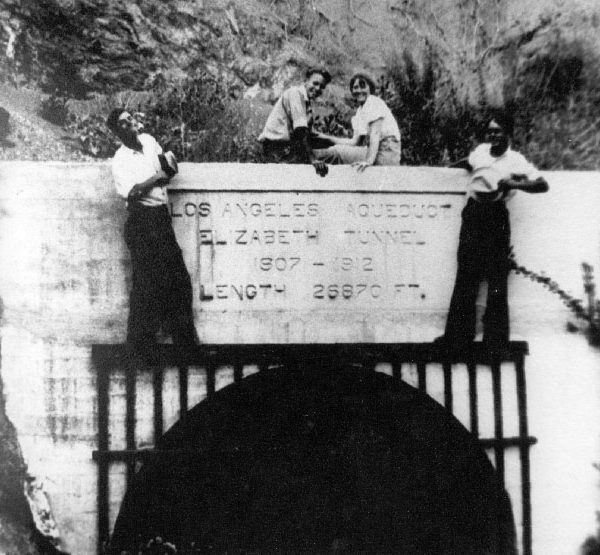

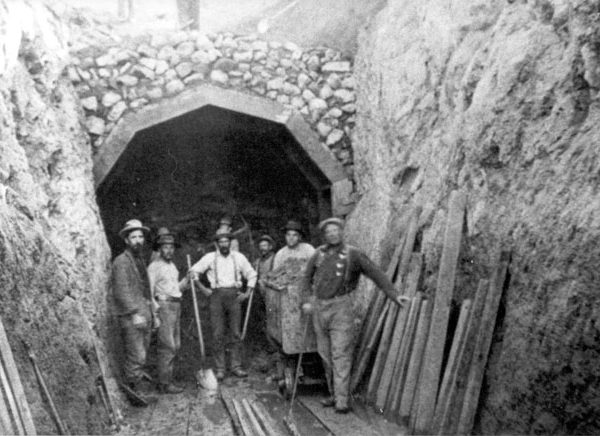

In the early twentieth century, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was built as a way to provide much-needed water to rapidly-growing Los Angeles. It was the brainchild of William Mulholland, an Irish immigrant who worked his way up from ditch cleaner to become the chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. In 1904 the Owens Valley-located between the Sierra Nevadas and the White Mountains-was targeted as the likely source of additional water for Los Angeles, a move that touched off the so-called “Owens Valley Water Wars” between city and valley residents. Nonetheless, the next year the project was publicly announced and Los Angeles residents approved a bond to pay for the aqueduct’s construction.

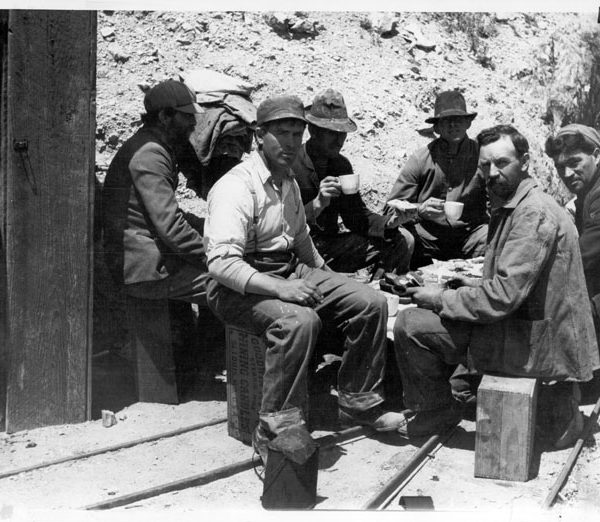

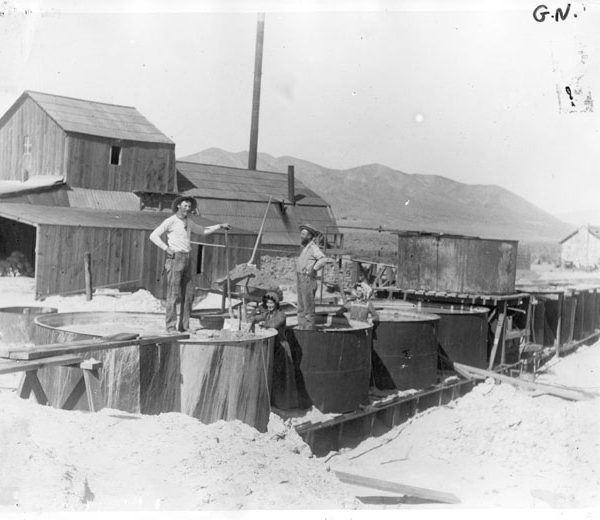

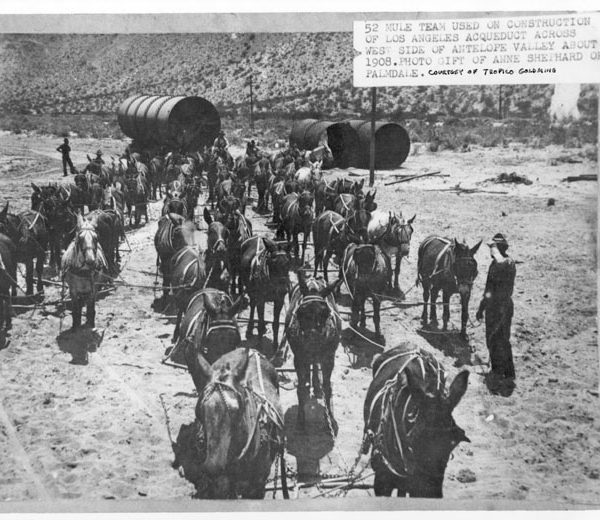

It took until 1913 to complete the 233-mile structure across mountains, hills, and desert, with some 6,000 men working round-the-clock as miners, laborers, and plasterers, using picks and shovels to dig trenches, drive tractors, put cement in place, and transport pipes. The project revived the economy of Antelope Valley communities Lancaster, Mojave, Fairmont, and Elizabeth Lake, whose farms and businesses had been decimated by a decade-long drought beginning in 1894. Becoming the country’s largest municipal water system in its day, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1913-ahead of schedule and under its projected $25.5 million budget-when it began transporting water from the Owens River into the San Fernando Valley near Sylmar and Mulholland.

The Valley’s first agricultural boom occurred during the 1880s and early 1890s, when heavy rainfall attracted homesteaders who successfully cultivated alfalfa, barley, wheat, and a variety of fruits and nuts. However, a serious drought between 1894 and 1904-the worst in Southern California’s recorded history-devastated farms, forcing many settlers to abandon their land in the valley. With the drought’s end came an agricultural resurgence after 1905 in the form of irrigation, thanks to pumps powered first by gasoline and later by electricity, which proved more reliable than the former reliance on artesian wells. Irrigation, besides allowing for the replanting of the crops that previously thrived, also allowed the large-scale cultivation of alfalfa, which by 1920 was the Antelope Valley’s major crop.

Between the 1880s and the late 1920s, farmers were also plagued by jackrabbits, who reproduced and ate crops so quickly that they made it impossible for many farmers to stay in business; Evan Evans, a settler and county road superintendent, noted that the rabbits were so thick that at night the ground appeared to be moving. To eradicate these pests, farmers held big jackrabbit drives in which horseback riders drove the rabbits into makeshift corrals, clubbed them to death, and then barbecued the meat; the events were considered a weekend sport that attracted locals and city folk who came by train from Los Angeles. Though communities such as Littlerock have retained their agricultural character, the Antelope Valley has undergone tremendous change and growth in the second half of the twentieth century with a shift from agriculture to defense and aerospace development.

California’s Gold Rush began southwest of the Antelope Valley, contrary to the popular belief that James Marshall found the first gold in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill in northern California. The big discovery occurred in 1842 at what was then called Live Oak Canyon when Francisco Lopez, stopping for lunch while searching for stray cattle, pulled some wild onions and found flakes of gold clinging to their roots.

In the subsequent gold rush, the canyon was named Placeritas, meaning “Little Placers,” and today is called Placerita Canyon. Gold rushers soon flocked to the canyon and took an estimated $100,000 of gold from the region before heading north to the more exciting discovery at Sutter’s Mill.

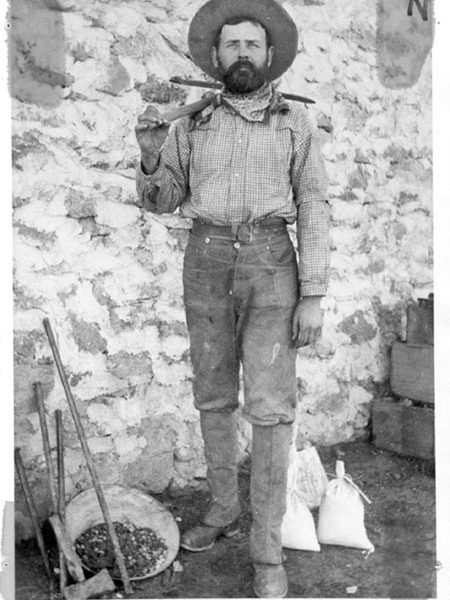

Mining changed the region’s history in profound ways, as gold seekers settled permanently in the valley’s southwestern corner during the 1850s and 1860s. The area further grew during the Civil War, as gold, silver, and copper were extracted from the Soledad Canyon region and Fremont’s Pass was enlarged to facilitate and speed up ore shipments. However, in a more sustained fashion mining helped valley residents survive the drought between 1894 and the Great Depression of the 1930s, though desert mining imposed numerous hardships that included high equipment costs, broken-down wagons, temperatures that swung between bone-chilling winters and scorching summers, fatal mine shaft accidents, a shortage of lumber for buildings and fuel for fires, looting in camps and supply stations, and lack of water. Mining continues today in and around the Antelope Valley, where besides gold, silver, and copper, the ores and minerals extracted over the years include antimony, borax, calcium, chloride, feldspar, granite, gypsum, iron, lead, lime, limestone, marble, potash, rotary mud, salt, silica, tungsten, uranium, volcanic rock, and zinc.

Tiburcio Vasquez was a legendary and much-feared 1870s California outlaw who was considered a hero by Californios and a villain by the Anglo population. Born in 1835 to a wealthy and respected family in Monterey, Vasquez was a well-educated teenager with a poetic flair when, following a fight at a dance in 1852, he and two other men were accused of killing a sheriff. The only one of the three to escape a mob lynching, Vasquez opted to live a life of crime rather than obey mainstream laws. Imprisoned twice for petty theft and stealing horses, upon release he and former prisoners formed a gang and held up stagecoaches, stole horses, robbed cattle, and otherwise cut a wide criminal swath throughout central and southern California.

The target of the greatest manhunt in California’s history, Vasquez eluded his captors for almost twenty years in mountainous and rural areas that included the vast Antelope Valley. There, he found an ideal rock fortress near Agua Dulce springs-a spot known today as Vasquez Rocks Park-that he used as a hiding place by passing himself off as horse buyer Ricardo Cantuga. In April 1874, with a $8,000 bounty on his head, Vasquez was caught by a posse near what is now the Hollywood Bowl, put on trial in San Jose, and hanged in 1875. More information about Tiburcio Vasquez can be found in the following sources:

Florence Leontine Lowe Barnes, nicknamed Pancho, was a colorful and fiercely independent socialite who made her name as a pioneering female pilot. Born in Pasadena in 1901, the high-spirited Florence thwarted the efforts of her fundamentalist parents to channel her energies in a conventional direction; though they arranged their debutante daughter’s marriage in 1921 to proper Episcopalian minister C. Ranken Barnes, she left him after receiving a half-million dollar inheritance following her mother’s 1924 death. Thus began her life as a freewheeling globe-trotter and hostess: she headed for South America on a luxury liner, returned to the United States to entertain movie stars and pilots such as Bette Davis and Amelia Earhart, crewed on a south-bound banana boat, and trekked across Mexico, where she indulged her rebellious streak by adopting the nickname “Pancho.”

A life-changing experience occurred in July 1928, when Pancho took her first flight out of Ross Airfield; the next week she bought a Travel Air 4000 aircraft and started taking flying lessons, and in September she made her first solo flight. From then on, flying became her passion and claim to fame, perhaps no surprise given her lineage as the granddaughter of Thaddeus S.C. Lowe, who during the Civil War commanded observation balloons for the Union Army. In 1930 alone, Pancho won the women’s world’s speed record of 196.19 miles per hour (beating the record previously held by Earhart), was the first woman to fly into Mexico’s interior, and won her first Tom Thumb race. Several years later she also started the Women’s Air Reserve and trained women in flight exercises, first aid, and parachute drops.

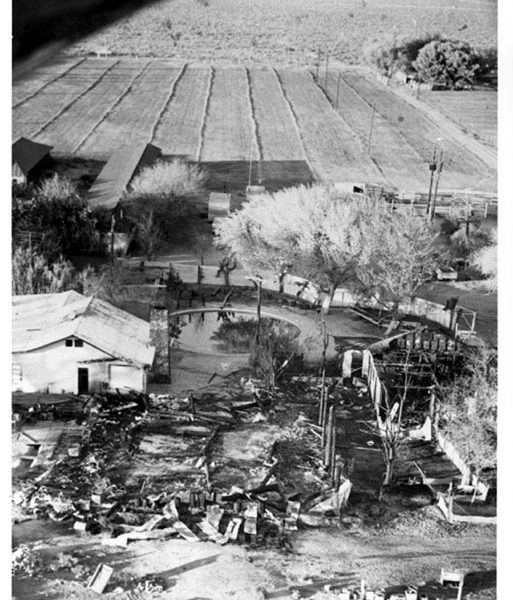

During the 1940s, the outspoken, cigar-smoking Pancho ran a tavern/inn sixty miles north of Los Angeles known as the Rancho Oro Verde (also known as the “Happy Bottom Riding Club”), which included Sunday brunches for pilots, exciting rodeos, training programs for civilian pilots, and Wednesday night dances; the inn was frequented by pilots and future astronauts testing aircraft at Edwards Air Force Base. Her fortunes took a bad turn during the 1950s and 1960s when the Air Force took her property for expansion and she suffered ill health, but circumstances improved about a decade before her death in 1975. Over the course of her eventful lifetime Pancho was also a barnstormer, movie stunt pilot and movie double, songwriter, and animal trainer. Valerie Bertinelli portrayed her in Pancho Barnes, a 1988 made-for-television movie.

The movie actor John Wayne-born in Winterset, Iowa, in 1907 as Marion Morrison-spent about two years of his childhood on a farm near Lancaster. He was the first-born child of Mary “Molly” Brown and Clyde “Doc” Morrison, who after being diagnosed with tuberculosis moved his family during the 1910s to an 80-acre homestead near Lancaster-roughly where the United Parcel Service is now located near Sierra Highway. As a child, Marion attended the old Lancaster Grammar School on Lancaster Boulevard, though school records show he had poor attendance and at age 12 was promoted only to the third grade. Doc, unsuccessful at farming, soon returned to his original profession as a pharmacist in Glendale, where he moved his family. Marion went on to attend the University of Southern California on a football scholarship and later became an actor who made more than 150 films. He died of cancer in 1979.

Frances Ethel Gumm, later known as Judy Garland, lived in Lancaster during part of her childhood. Born in 1922 in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, Frances and her family-father Frank, mother Ethel, and sisters Mary Jane and Virginia-moved to southern California in 1926. Frank, in search of a movie theater where his three daughters could sing and dance, looked first in Glendale and then West Hollywood before buying the 500-seat Lancaster Theater. He renovated the interior, built a box office, installed air conditioning, changed the name to the Valley Theatre, and thus created a venue where the “Gumm Sisters” could perform on a regular basis, with their mother as agent and manager. While living in Lancaster before relocating to Los Angeles in 1933, the Gumm family lived in three houses, one near the high school and two on Cedar Avenue.

Though much of Frances’s early stage and theater experience took place in Lancaster, she and her family performed beyond the Antelope Valley as well, in Los Angeles and outlying towns. Frances’ stage name changed several times-and included Frances Gayne, Alice Gumm, and Baby Gumm-before it became Judy Garland. She went on to become a prolific and versatile entertainer, whose oeuvre included 32 movies, one Academy award and two nominations, and thousands of theater, nightclub, television, and radio performances. She is best known for her role as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz and her acting in Andy Hardy movies. In her personal life she was beset with emotional problems, however, and she died in 1969 at age 47, apparently from an accidental sleeping pill overdose. One of Lancaster’s most famous residents, her childhood footprints are imprinted in a cement sidewalk slab now located in the backyard of the city’s historic Western Hotel.

Today it is hard to imagine large groups of Native Americans living off the land in the Antelope Valley. Hundreds of years ago, however, the landscape of the Antelope Valley was very different. Vast plains of tall native bunch grass covered the valley floor and active springs and pools were plentiful. The lush vegetation and abundant water supply supported many types of wildlife which are no longer found in the valley. Archaeological evidence from what appear to be several major village sites indicate that substantial numbers of Indians occupied the valley floor year round at one time. Major trade routes from the coast to the eastern Mojave and Southwest, as well as north-south routes from the Central Valley and Owens Valley to the Los Angeles Basin also crossed the Valley.

Archaeologists believe that Native Americans have been living in, or at least visiting, the Antelope Valley for at least 11,000 years before the present. Over time, many cultural groups have passed through the Valley and left their mark. The original inhabitants were Paleoindians. These peoples were probably hunters of large game animals that have since become extinct. Among their weapons were spears with fluted projectile points. Little is known of the culture of these original people and only their artifacts survived.

From 9000 to 7000 years ago, as the Ice Age ended, great lakes formed in the Valley. Evidence exists of large groups living near these lakes. Many grinding tools have been found from this era pointing toward more dependence on plants for food, however, hunting remained an important activity. Many archaeologists believe that during this period, the atlatl (spear thrower) became more important as hunting activities became centered on faster game animals such as dear and antelope. Some people have speculated that these early people may have been Hokan speakers, the language ancestral to present day groups like the Chumash, Pomo, and Dieguenó. These groups may have formed the oldest semi-permanent settlements in the Great Basin.

During the period from 6000 to 4000 years ago, larger groups began to establish more permanent settlements. Game animals became smaller as evidenced by the increased use of dart points and other archaeological evidence. Plant processing also became more important in everyday life. As these settlements became more advanced toward the end of the period, a complex religious life began to emerge as well.

Starting about 4000 years ago and lasting until 1500 years ago, the people of the Antelope Valley became seasonal hunters. The mountain sheep was of major significance in this culture. Many of the rock art sites throughout the Coso Mountain Range near present day Ridgecrest appear to celebrate hunting and the mountain sheep. Archaeologists theorize that the rock art constituted a form of “hunting magic.” These peoples often had summer and winter camps which were spread throughout the Antelope Valley and nearby mountains. These camps helped in the seasonal gathering of food. The ceremonial life that evolved to produce such beautiful rock art is little understood.

After about 1500 to 1000 years ago, people depended more on gathering than on hunting. Hunting itself also changed considerably during this period. The invention of the bow and arrow forever changed the way the people hunted. Fewer men could acquire game more quickly and with more stealth.

From the period 1000 years ago, and perhaps earlier, until the Spanish arrived in California, the culture of the Antelope Valley changed dramatically. It is believed that this is the time the “Shoshonean Wedge” swept through the Great Basin and California. The Uto-Aztecan (Shoshonean) speakers more or less took over the Great Basin and parts of Southern California during this period. The details of their origins or how rapidly they spread remain controversial.

More is known about these people than about those that came before them. The cultures that developed during this time are what we today call the Great Basin people. They lived in summer and winter homes. They created the great communal grinding stones found throughout the Antelope Valley. They supplemented their diet of acorns and piñon nuts with small game and deer. These are the people the Spanish first encountered when they began to explore the Antelope Valley.

When the Spanish and other Europeans began to come to California about 400 years ago, the Antelope Valley’s population had already begun to decline, probably because of the increasingly arid climate. Groups of Serrano, Kitanemuk, Tataviam, and Kawaiisu were living in and around the Valley, but not in great numbers. Many of these groups shared the Paiute culture with the people living further north in the Owens Valley. Some Chumash influence also existed in the Valley, as evidenced by different language groups. Trading among the different groups was extensive. Obsidian from the Mono Lake area and sea shells from the coast are still frequently found today throughout the Valley.

The first fully documented contact with the people of the Antelope Valley came in 1776 when a Franciscan priest, Father Francisco Garcés began a trip to Monterey through the Mojave Desert. Garcés’s diary of the trip has been used by many scholars to identify the people, cultures, and language groups living in the Antelope Valley at this time. For several years, the contact with the Spanish was limited and benign, however, increasingly the people of the Valley began to be “resettled” to the San Fernando Mission. In 1808, the Spanish sent a military expedition into the Valley. There is no documentation of any violence during this expedition, but it began the continual and eventually deadly contact with the Spanish. In 1811, Mission records indicate the “resettlement” of two entire villages.

The slow decline in the population of the Antelope Valley followed that of other native Californian societies. Disease spread by contact with the missions and forced labor continued to take its toll. To the Europeans, tribal and clan affiliation held little meaning. As with many California cultures, the old ways began to die along with the people.

Many revolts were staged against the Spanish, as various tribal groups attempted to free themselves from the oppression of the government-sanctioned Mission system. Only a few succeeded, and then only for short periods. In the mean time, the Spanish, by then under the flag of the Mexican government, and other Europeans began to establish farms and ranches in Southern California, thus dislocating the original people. By the time California was transferred from Mexico to the United States in 1848, the people of the Antelope Valley were losing their struggle for survival.

While the Gold Rush did not directly impact the people of Southern California, it was important in many ways. The massacres of many tribes to the north cut off centuries old trading patterns. As more people came to California in search of gold, many filtered south for the rich farming land of the San Joaquin Valley. The United States government began a policy of relocating Native Americans to give the best land to the European settlers. In 1853, Fort Tejon was established in the mountains on the western edge of the Antelope Valley. The United States government established a reservation there to “protect the Indians.” By 1864, the 1000 people living there had deserted the fort in an attempt to return to their ancestral lands in the Tehachapi Mountains and in the Antelope Valley. However, the government continued its reservation and relocation program well into the twentieth century. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most native groups remaining in the Antelope Valley simply faded into the European culture growing up around them. More information about native populations in the Antelope Valley can be found in:

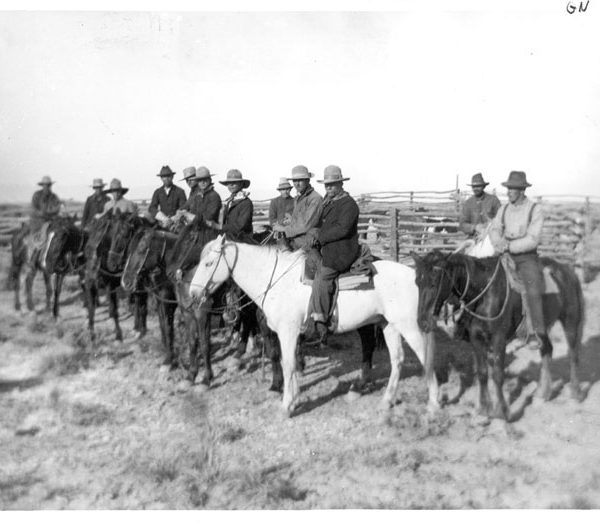

Cowboys and cattle ranching began in the Antelope Valley as early as the 1840s and became more prevalent in the following decade after the gold rush led to a demand for beef. One of the most important jobs for cowboys was to round up calves in the spring-and perhaps again in the fall-and to brand, castrate, dehorn, and vaccinate them. Among the best known cowboys were Ted Atmore, Emery Kidd, and Forrest Patterson. Cattle ranching was especially important in the region between 1886 and 1910, though it was hurt by the drought between 1894 and 1904. Cowboys and farmers sparred over a number of factors, including competition for land and crop damage by livestock; the tension prompted farmers to erect fences to keep cattle out and led ranchers to discourage prospective farmers from settling in the region. By the 1920s the cattle industry had slowed down tremendously in the valley due to a growing population and disputes with sheep herders and alfalfa growers.

Edward Fitzgerald Beale-a Mexican War veteran who traveled to Washington, D.C., as the first person to report news of California’s gold discovery-came up with the idea of using camels to reach distant Western military posts. After he successfully pitched the idea to War Secretary Jefferson Davis, Congress voted in 1855 to spend $30,000 for an experimental American Camel Corps, and the following year the camels started to arrive at the mouth of the Mississippi River. General Beale and a team of men led the camels from New Orleans to Fort Tejon, where they subjected the animals to various tests but ultimately found the experiment problematic. Ultimately, some camels headed out into the desert and the rest were sold at auction by the U.S. Army-and with the 1937 demise of their last descendant, “Topsy,” the American Camel Corps died a quiet death.

The San Andreas Fault, one of the world’s most heavily scrutinized tectonic plate boundaries, extends along the Antelope Valley’s entire southern slope. Although the fault is perhaps best known for the 1906 earthquake that caused the great San Francisco fire, one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded in U.S. history occurred when a major rupture occurred on the fault’s line at Fort Tejon on January 9, 1857. As a result of the quake, which registered about 8.0 on the Richter scale and is estimated to have lasted up to three minutes, the Kern River reversed course and overran its banks by four feet, water from the Mokelumne River was thrown on the banks, and Fort Tejon-located at the epicenter-was severely damaged. Because the affected area was sparsely populated at the time, only two people died; today, the same earthquake would probably kill many more people in communities such as Frazier Park, Palmdale, Taft, and Wrightwood, all built on or near the area that ruptured in 1857.

During the 1870s, completion of a Southern Pacific Railroad line through Antelope Valley changed the region from an isolated basin to a magnet for settlers. The railroad had been looking for an inland railroad route between San Francisco and Los Angeles since 1853, following passage the previous year of the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroad Act to give railroad companies land grants to encourage settlement near train routes and distribute public land to make family farms affordable. The Southern Pacific finished its route through the valley in 1876 and settlers soon flocked to the region and established homesteads near surface water, thus launching a boom growth period.