Gardena

Community History

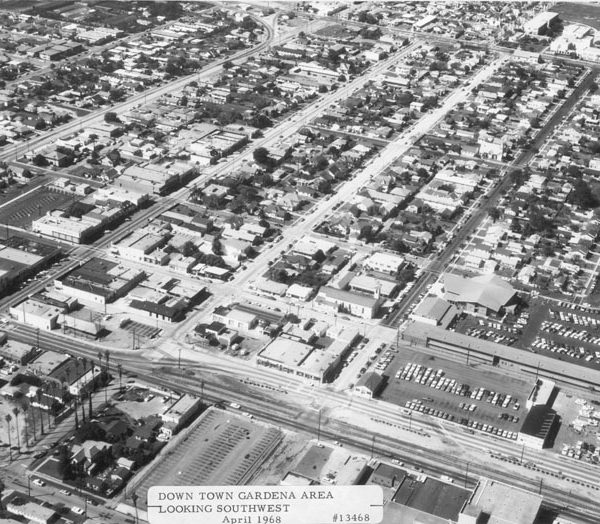

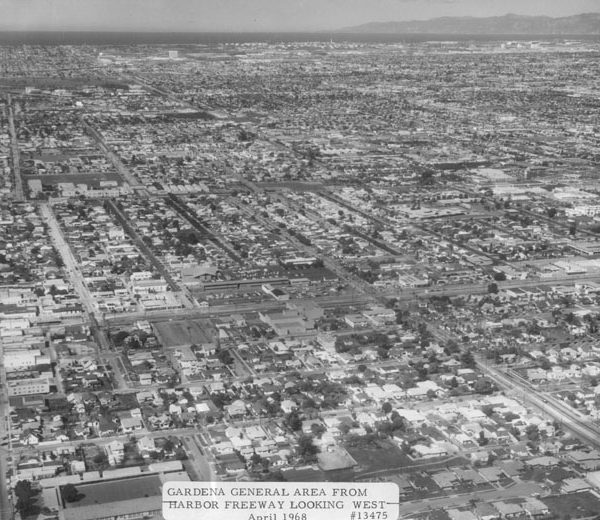

Gardena, once the berry-growing capital of southern California, is today called the “Freeway City” because it is bordered by the Artesia, Harbor, and San Diego freeways to its south, east, and west, respectively. Its modern-day urban designation is a far cry from Gardena’s early reputation as a “garden spot,” a lush oasis of greenery fed by the waters of the Dominguez Slough. Long before it was officially incorporated in 1930 by combining the rural communities of Moneta and Strawberry Park, Gardena was known first by Gabrielino Indians and later Spanish and American settlers as a long green stretch of land amidst coastal sage scrub.

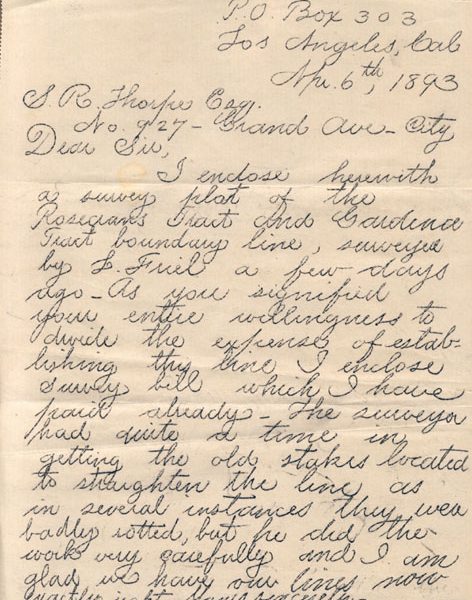

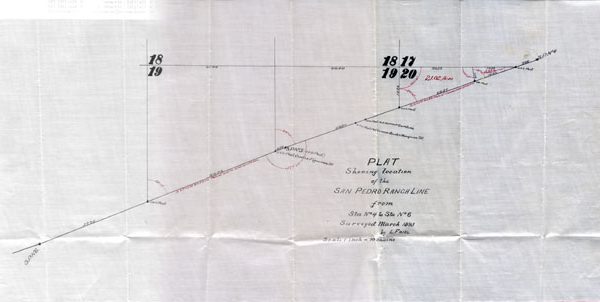

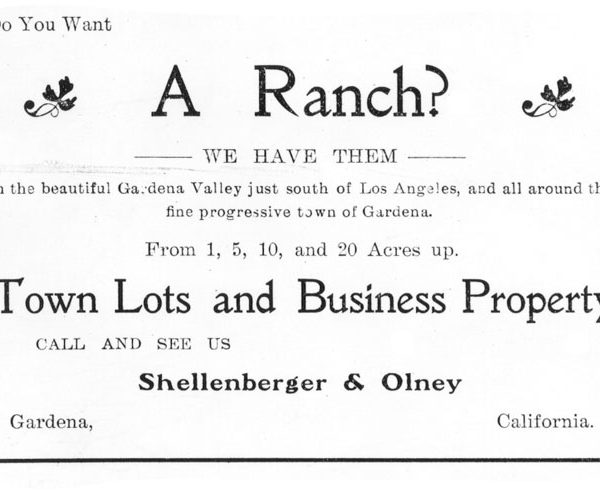

The community originally evolved from part of the roughly 43,000-acre Spanish land grant, the Rancho San Pedro, given to Juan Jose Dominguez around 1800. The site was later named the Rosecrans Rancho after Union Army Major General William Starke Rosecrans, who bought 16,000 acres following the Civil War. This land would later be bordered on the north by Florence Avenue, on the south by Redondo Beach Boulevard, on the east by Central Avenue, and on the west by Arlington Avenue. After the property changed hands several times, early Gardena was laid out with Figueroa and 161st streets at its center, the idea being that the Los Angeles and Redondo Railway would pass next to it when extended south between those two communities. When the route instead came in along Vermont Avenue, the community moved to accommodate the change.

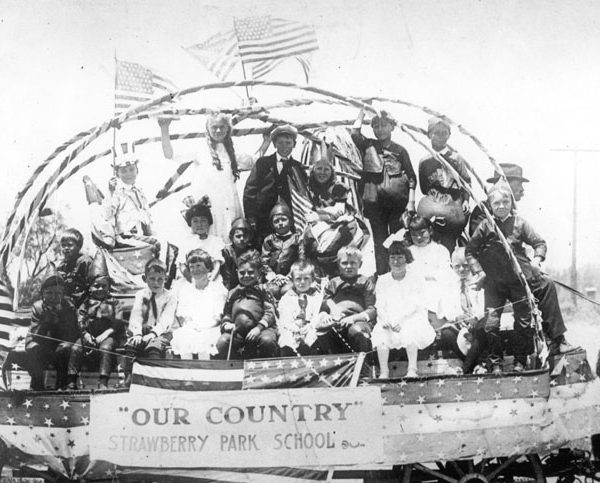

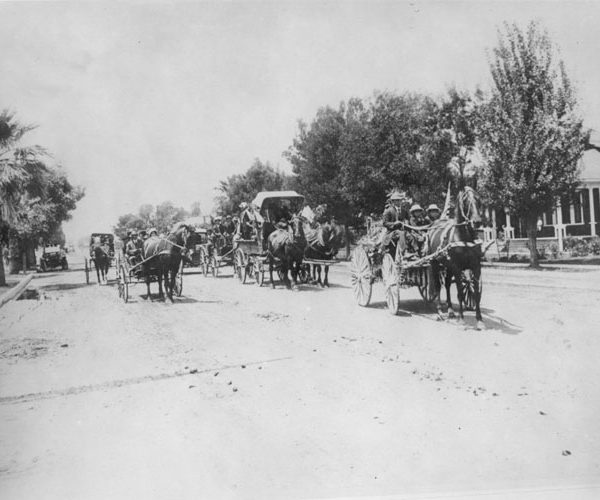

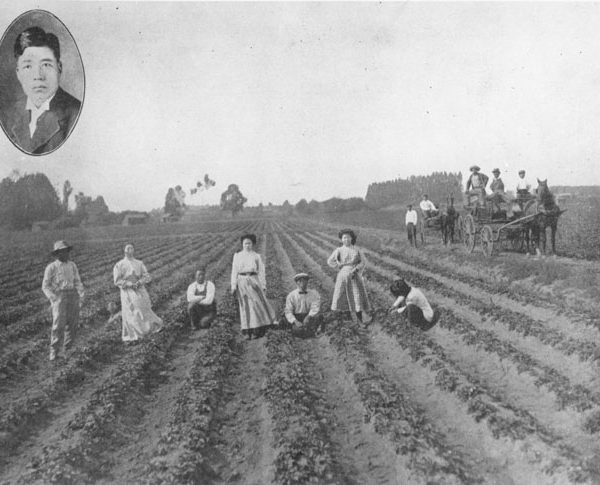

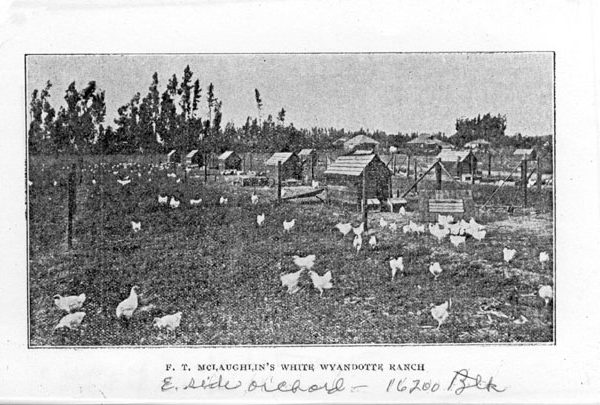

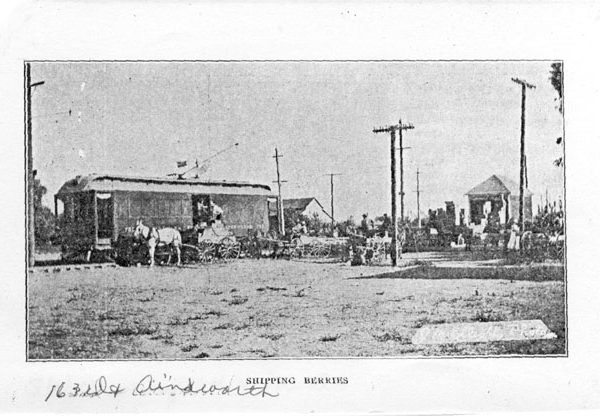

Farming became Gardena’s main industry early in the twentieth century, though berries, especially strawberries, were its claim to fame. The community became known as “Berryland,” and was renowned for its Strawberry Day Festival and parade every May. The berry industry dwindled with World War I, when land was used first for other crops and then later for development.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

The first Spanish settlers arrived in the area in the late 1700s. Nearly all the territory of what would become Gardena Valley was part of Rancho San Pedro, 43,119 acres that Juan Jose Dominguez received between 1784 and 1800 for his military service. This property-the third Spanish land grant and one of the largest made-was used for raising first sheep and then cattle.

Later the site became part of Rancho San Pedro, with the patent confirming the land grant signed by President James Buchanan in December 1858. After the Civil War, Union Army Major General William Starke Rosecrans in 1869 bought 16,000 acres for $2.50 an acre, a low price possibly because the land was deemed worthless for lack of a spring for water. The ranch, dubbed “Rosecrans Rancho,” was bordered by what later was Florence Avenue on the north, Redondo Beach Boulevard on the south, Central Avenue on the east, and Arlington Avenue on the west.

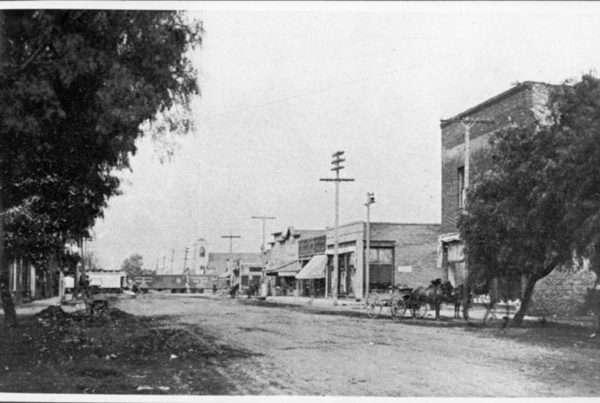

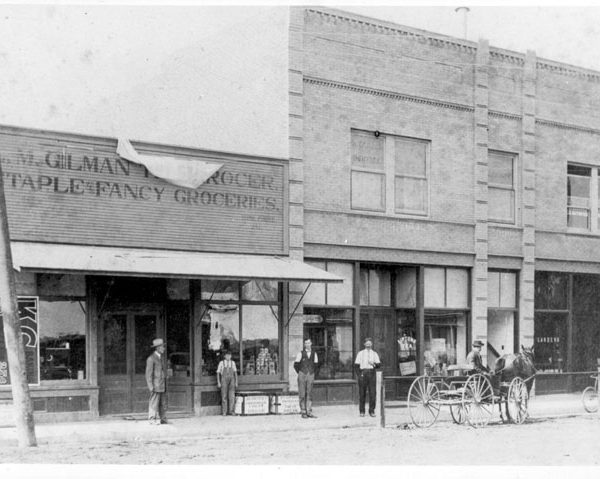

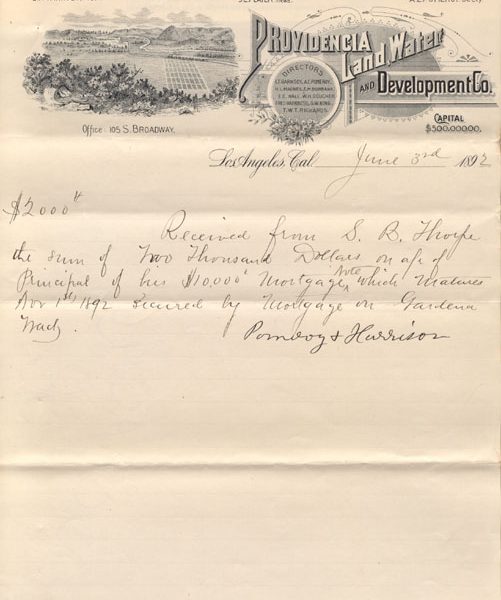

The Rosecrans property was sold in the early 1870s for $50 an acre and then broken into parcels. One of those became the 800-acre McDonald Ranch, whose ranch buildings stood at today’s intersection of 161st and Figueroa streets. Gardena proper began in 1887 when the Pomeroy & Harrison real estate developers subdivided the ranch, and-anticipating that the coming of the Los Angeles and Redondo Railway would stretch south on Figueroa Street-planned the new community with the ranch buildings at its two-acre center.

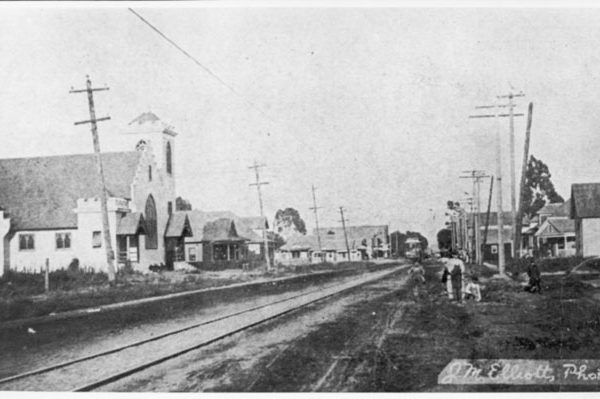

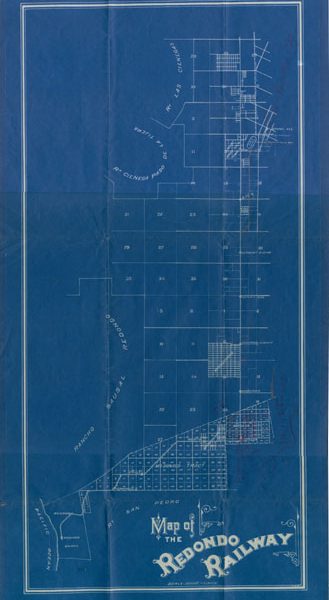

As it turned out, the real estate people were proved wrong. The railway, which opened in April 1890, was built through Gardena-but rather than going down Figueroa Street it followed Vermont Avenue. Undaunted, the residents of the fledgling community moved themselves and the town’s core from its original location to the intersection of Vermont and 166th streets in 1889, the year before the railroad opened in April 1890-and that’s where Gardena’s modern-day center still is.

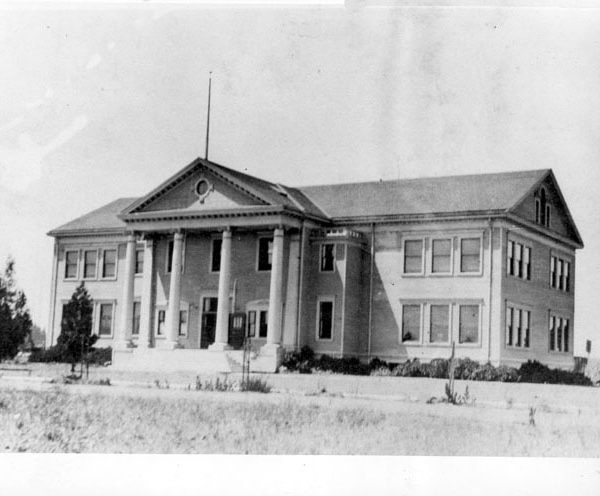

Gardena, named by the daughter of early settler Spencer Thorpe in honor of being a “garden spot,” was incorporated on September 11, 1930 with the blending of rural communities Moneta and Strawberry Park. Its new municipal status represented a response to the so-called “Alondra Park incident” that threatened to burden taxpayers with an enormous debt.

Rosecrans, a Major General in the Union Army, was born in Ohio in 1819 of Dutch descendants who had moved first to Pennsylvania before heading to Ohio. An 1842 graduate of West Point, Rosecrans after the Civil War came to Southern California to invest in land and in 1869 bought 16,000 acres of what became “Rosecrans Rancho” for $2.50 an acre. Though this 25-square-mile tract of land was flat and fertile, it was considered to be of no value, possibly because it lacked springs. However, it was from Rosecrans’ property that Gardena ultimately emerged.

After relocating to California, the Rosecrans was often away on business. In 1868 he was appointed U.S. Minister to Mexico; in 1869 he became one of the incorporators of the Southern Pacific Railroad; he was elected to the United States Congress in 1881 and again in 1884; and in 1885 he was appointed Registrar of the U.S. Treasury. He retired in 1893 and died near Redondo in 1898. His son, Carl F. Rosecrans, became owner of Rosecrans Rancho and was the major catalyst for the building of the San Pedro rail line through Gardena between Los Angeles and San Pedro.

Gardena was dubbed “Berryland” for its acres of strawberries as well as raspberries and blackberries grown year-round a century ago. The community owes its early reputation as a farming community to the Dominguez Slough, whose waters made Gardena an oasis amid an otherwise barren landscape. Among the crops grown there besides berries were tomatoes, alfalfa, and barley.

Railroads put Gardena on the map near the end of the nineteenth century, after the Los Angeles area underwent a tremendous real-estate boom in 1886 and 1887. The Gardena Valley’s first railway line, which ran from Agricultural Park in Los Angeles to the townsite of Rosecrans (roughly halfway to Redondo), was the “Rosecrans Rapid Transit Railway,” built in 1887 by real estate men Emil D’Artois and Walter L. Webb. After a year of intermittent rail service, they discontinued rail travel in the summer of 1888; by the following spring, the railroad was bought and operated by the Redondo Railway Company. The company wasted no time building a roughly 20-mile rail line between Los Angeles and Redondo, which opened for business April 11, 1890, thus prompting the moving of downtown Gardena from Figueroa Street to Vermont Avenue.

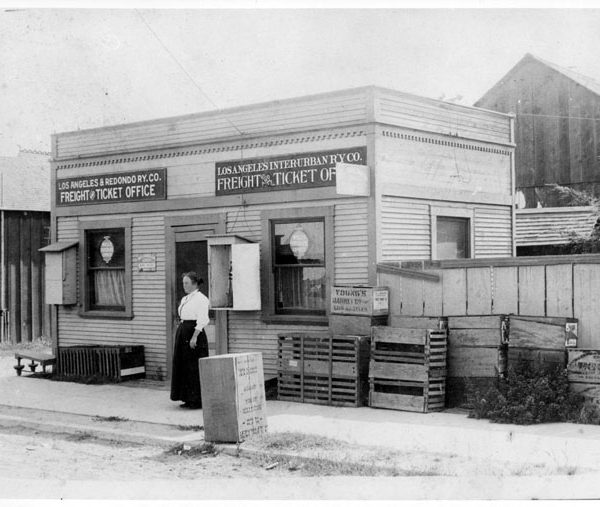

The early twentieth century was a time of great passenger railroad growth in and around Gardena. In 1903, a line connecting Los Angeles and San Pedro via Gardena started operating; it was built by the California Pacific Railway Company, which the following year was bought by the Los Angeles Inter-Urban Railway Company. In 1907, the Los Angeles and Redondo Railway (formerly the Redondo Railway Company) built and started a Moneta Avenue line between East Athens and Strawberry Park.

And in 1912, the Pacific Electric Railway Company completed a line through Gardena between Watts and the Redondo Beach Line. By then, Pacific Electric had also acquired the other lines through consolidation. In 1940, Pacific Electric’s rail passenger service through Gardena ended and was replaced by buses. Today, the only trains passing through Gardena are diesel freight cars.

Japanese immigrants were a key part of Gardena’s farm community during Gardena’s early years, and their influence remains visible today. In 1911, the Japanese Association founded the Moneta Japanese Institute at the intersection of New York and Market streets, and with donations from the Japanese-American community paid for the lots, a school house, and teachers’ living quarters. Five years later the Parents’ Association founded the Gardena Japanese School. Gardena’s Japanese population was, along with 110,000 other people of Japanese ancestry, moved from Pacific coastal communities to relocation camps in the middle of the United States in the spring and summer of 1942 as a military security measure during World War II.

The Dominguez Slough was a serpentine inland freshwater lake created from rainwater runoff, and which made Gardena a well-known “garden spot” in Southern California. The slough wound its way to San Pedro’s mud flats and for many years in Gardena’s early history provided an excellent recreational destination for hunters, fishermen, young boys wanting to play in the great outdoors, and people on vacation who swam and boated there. During the 1920s the slough was drained and filled in order to extend Vermont Avenue in Gardena.

Gardena was once known as “Berryland” for its production of strawberries as well as raspberries and blackberries, and had a reputation as the berry capital of Southern California. It was especially well-known for its annual Strawberry Day Festival and parade held each May, when each visitor received a free box of strawberries. The community of Strawberry Park also evolved north of Gardena. The berry industry fell off during World War I as other crops were cultivated for the war effort, and afterward the community’s development grew to eclipse much of the former farmland on which the berries were grown. Much of the land on which the berries were grown was leased by Japanese immigrants who cultivated the strawberries with artesian well water.

Based on archaeological digs in and around Gardena, Gabrielino (Tongva) Indians hunted and fished near Gardena, though they did not live there. Numerous skeletons of Native Americans have been dug up on a small mound on the southern edge of the Dominguez Slough, and based on shells found there and the burial site location, the remains are thought to be those of the prehistoric Tongva culture, considered the wealthiest, most dominant, and most progressive of all the Shoshoneans. They were not strictly local Indians, but rather lived as well in Los Angeles County south of Sierra Madre, the Santa Catalina and San Clemente islands, and half of Orange County.

Gabrielino Tongva Springs Foundation

Gabrieleno/Tongva Band of Mission Indians of San Gabriel

Gabrieleno/Tongva Band of Mission Indians of San Gabriel – Links

The Gardena City Clerk’s Office has a photograph album donated by Sumitomo Bank containing historic photographs of Gardena. Several historic Gardena photographs are also available at the Seaver Center for Western History Research at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and at the Los Angeles Public Library.

Places to Visit:

Gardena City Hall

City Clerk’s Office

1700 W. 162nd Street

Gardena, California 90247

310.217.9500

Los Angeles Public Library – Photo Collection

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County – Seaver Center

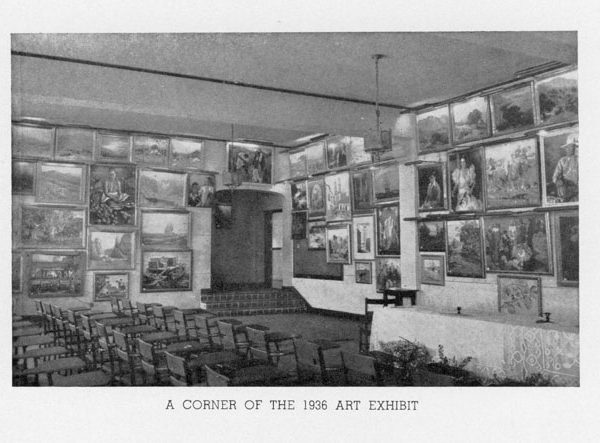

The Gardena High School art collection began as the gift of a single painting to the high school by the senior class of 1919. The practice of purchasing a painting for Gardena High School as a senior class gift continued in subsequent years, until the school became the owner of a major collection of plein air paintings by many of California’s greatest Impressionist painters. Eventually, however, the collection languished under substandard storage conditions and was in danger of being lost. A grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation prevented this from happening. CSU Dominguez Hills directed the restoration of the collection and organized an exhibit that opened at the University Art Gallery in January 1999.