Catalina Island

Community History

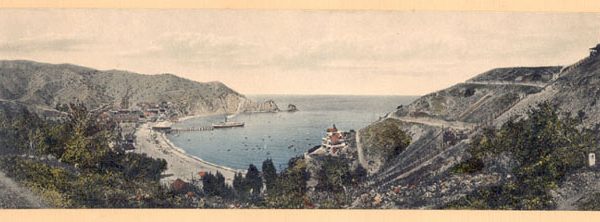

One of the southern Channel Islands, Santa Catalina lies the closest of the group to mainland California. Its rugged landscape boasts peaks reaching 2,000 feet above sea level, while its beaches are limited, adhering primarily to the mouths of canyons. The tiny island has nevertheless been inhabited for nearly 7,000 years, with its original Native American occupants probably having paddled their plank canoes from the mainland’s shores to settle the rocky land mass and develop a marine-based culture.

The Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo became the first European to visit the island in 1542. During the next several centuries, other Spaniards stopped at the island, but it was not until the late 1700s that life was dramatically altered for the island’s native peoples, when Spanish colonization of the California coast began in earnest and most of the island’s population, by choice or compulsion, relocated to the mainland during the following decades.

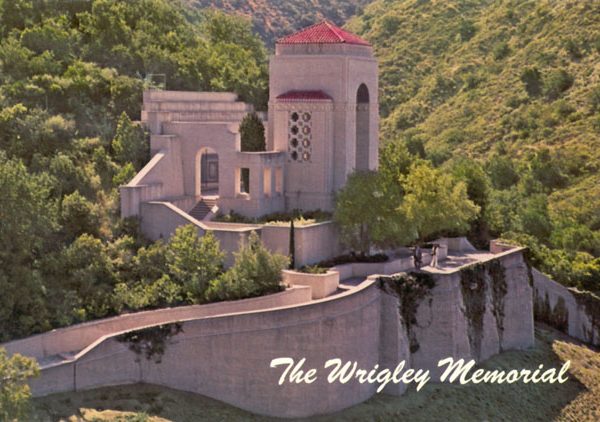

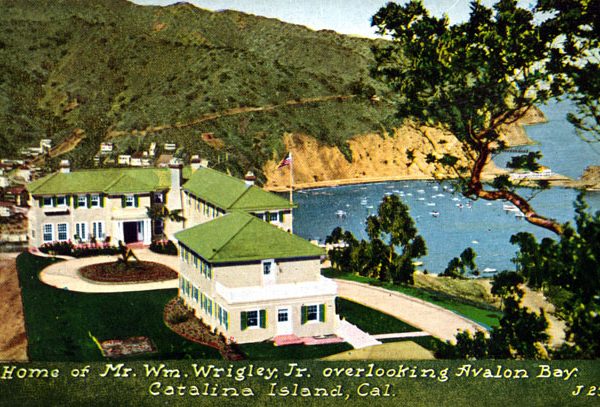

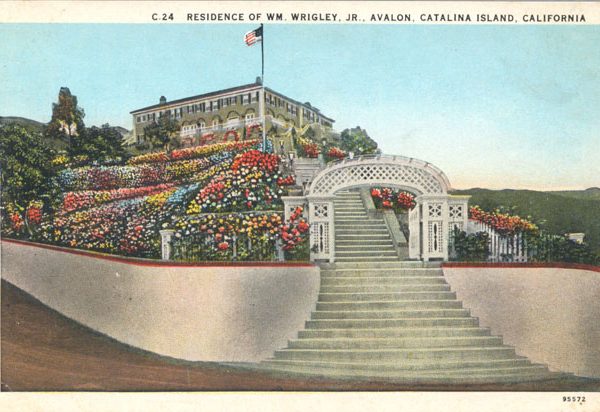

In 1846, shortly before the United States assumed control of California and its islands, the Mexican government granted ownership of the island to a private citizen. Changing hands a number of times during the late 1800s and early 1900s, the island has belonged to the Wrigley family since 1919. Settlers on Catalina Island raised sheep and cattle in the mid 1800s, introducing a ranching industry that continued in some form until the mid 1950s. Mining and the occasional use of the island by the U.S. government during wartime have also colored its history.

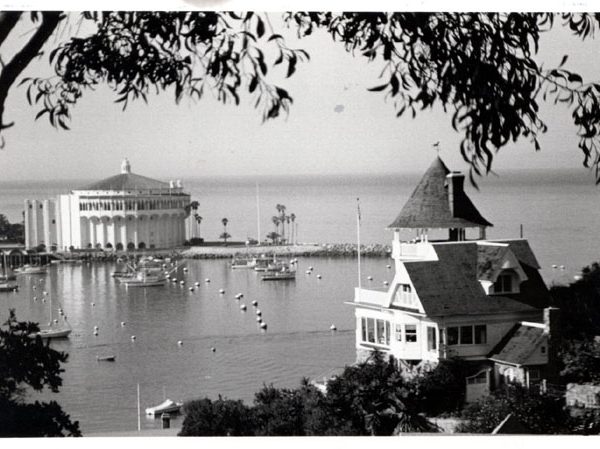

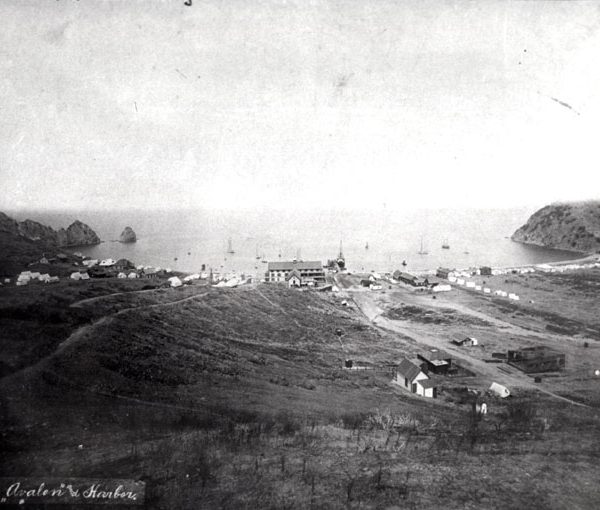

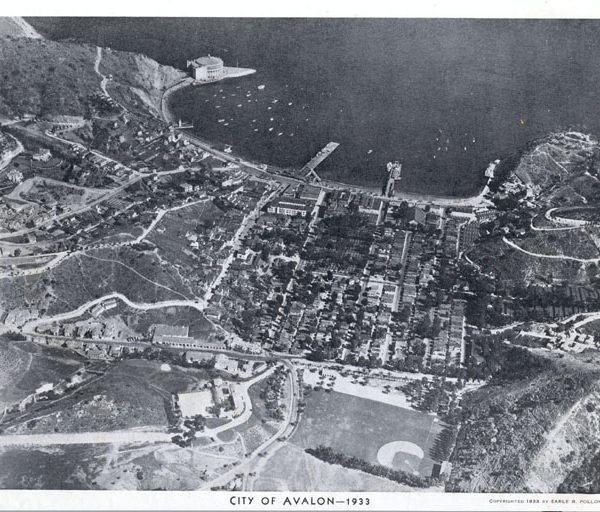

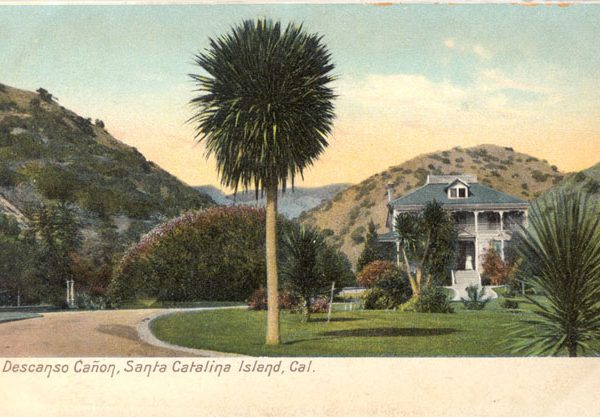

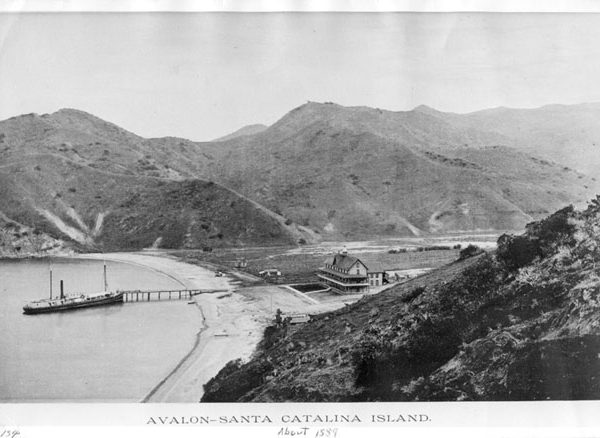

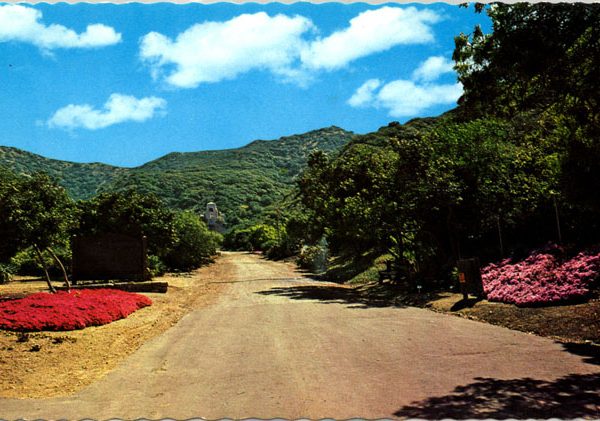

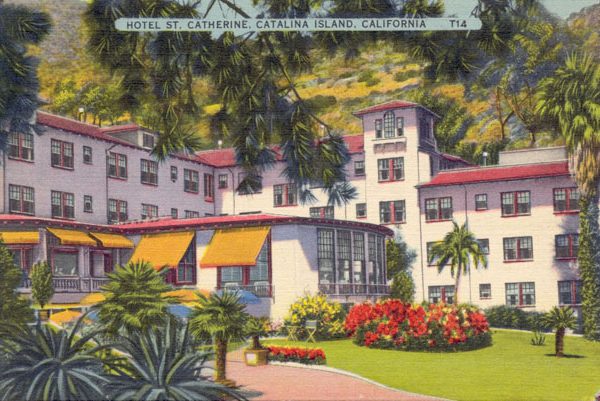

Most importantly for its future, in the late 1880s owner George Shatto embarked on a campaign to turn Catalina Island into a tourist destination, planning and building the town of Avalon as the focal point of the island and hub of this activity. Successive owners have nurtured his idea, constructing hotels, golf courses, and new tourist attractions and encouraging hunting, fishing, and other outdoor pursuits, helping to make Catalina Island the resort it is today.

Image Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

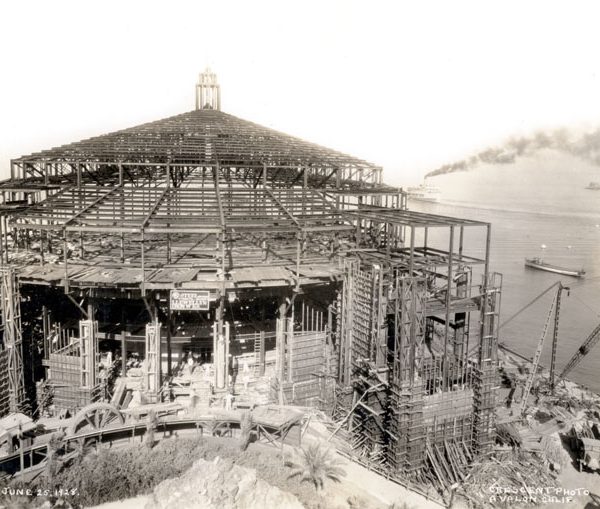

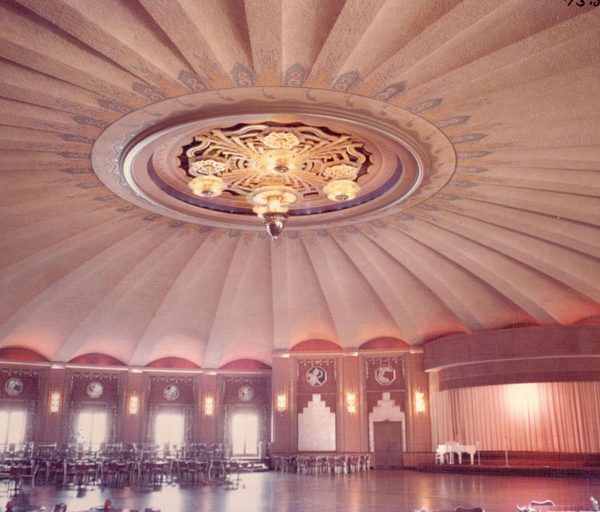

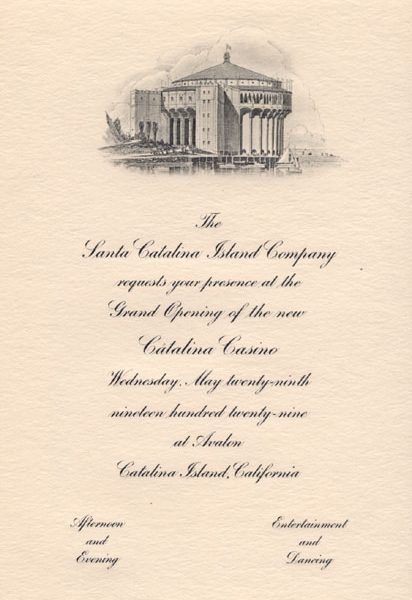

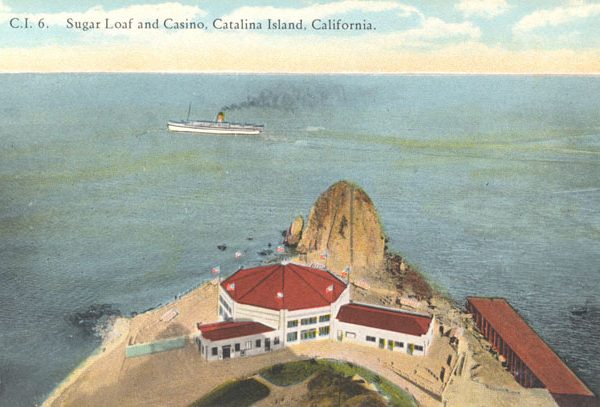

The building was completed in May, 1929. It took fourteen months to build, at a cost of $2 million.

The building was designed by Architects Walter Webber and Sumner A. Spaulding.

From 1920-1928, the octagonal Sugarloaf Casino was on the same site. It was a dance pavilion. It was also used as a roller skating rink, school, and restaurant. When it was torn down to make room for the current Casino Building, the steel framework was moved to the Bird Park where it became the main aviary. Sugarloaf Rock at the end of the point was blasted away in March, 1929, to enhance the view of the new Casino building.

Casino is an Italian word meaning “place of entertainment” or “social gathering place.” The Casino was built to house a state-of-the-art (for that time) theater and ballroom.

The best and only book is The Casino by Patricia Anne Moore (1979, revised 1999). This book can be viewed at the Avalon Library and purchased at the Santa Catalina Island Museum

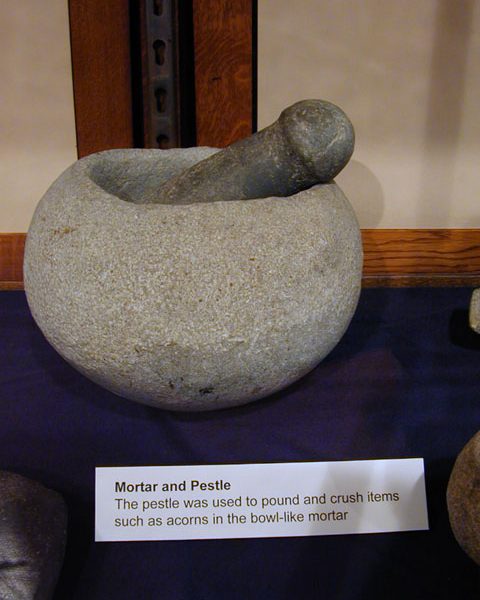

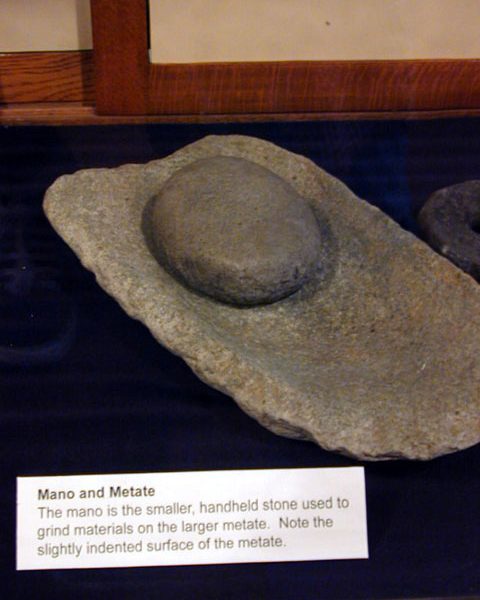

Native Americans who lived in the Los Angeles area and the Southern Channel Islands (including Santa Catalina Island) spoke a language distinct from their neighbors to the North and South of them. They have come to be known as the Gabrielino, because many of those who survived European diseases and the disruption on their normal trade patterns and culture went to the Mission San Gabriel in Los Angeles, some forcibly and some willingly. The most recent radiocarbon dating indicates human habitation of the Island for approximately 7,000 years before present. Other Channel Islands have found even earlier dates.

The Native Americans who lived here at the time the Spanish found them called Catalina Island “Pemú’nga” (most current spelling based on linguistic research of scholars; there are no fluent speakers of the Gabrielino language). We’re not sure when the last native Gabrielino went to the missions, but the missions’ baptismal records show Islander baptisms until the 1820s. Today one mainland group of Gabrielino ancestry, located in the San Gabriel area, calls themselves “Gabrielino/Tongva.” The United States government has not yet formally recognized any of the Gabrielino groups.

Catalina Island is 21 miles long and 8 miles wide at the widest point, and about _ mile wide at the Isthmus. Its perimeter of 54 miles encompasses approximately 47,884 acres or about 76 square miles. The highest point on the Island is Mt. Orizaba at 2,097 feet. It is 26 miles from Avalon to San Pedro and 21 miles from Arrow Point on Catalina to Point Vicente on the mainland. The Catalina Channel is about 3 miles deep.

Catalina Island has a few small communities, such as Two Harbors on the Isthmus, but 2.6 square mile Avalon is the only incorporated city. Prior to the annexation of Pebbly Beach and Avalon Canyon in late 1997, Avalon was one square mile in size.

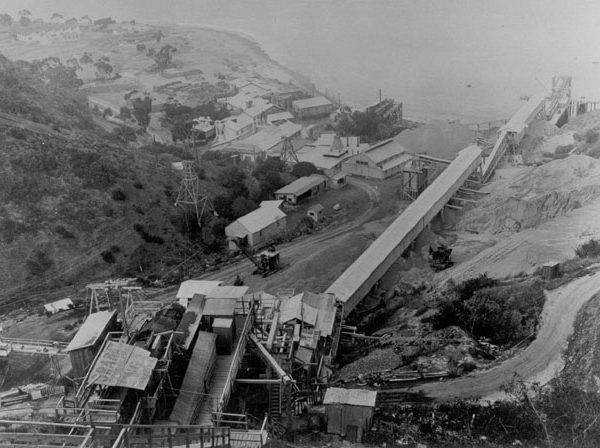

Tourism and quarrying are the Island’s main industries. In the 1930s, Catalina Island also had a pottery factory and a furniture factory. In the 1860s and the 1920s, a small mining industry briefly existed on the island. Miners discovered silver in 1864, but when the Army occupied the island that same year, all but a few miners with substantial claims were forced to leave. In the 1920s, William Wrigley, Jr., by then owner of the island, opened several mines which produced lead, zinc, and silver. The mines were closed when the price of silver dropped. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, ranchers raised sheep and cattle on the Island. The first ranch was established in 1846, but ranching died out in the 1950s when it was no longer profitable.

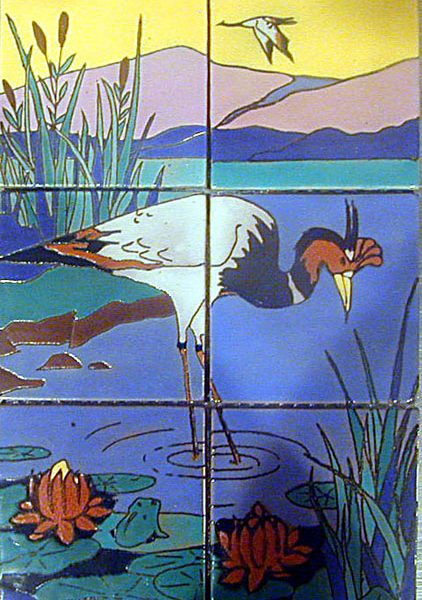

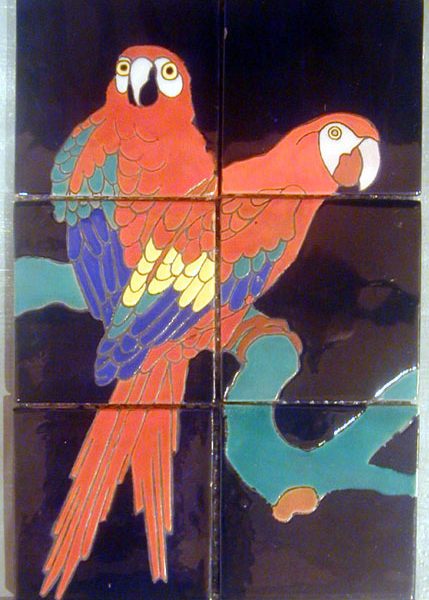

The Catalina Island Tile and Pottery factory operated from 1927 to 1937. It was established by the Santa Catalina Island Company to take advantage of the clay deposits discovered by William Wrigley, Jr. and David M. Renton and, more importantly, to use these to help reduce construction costs on the Island by producing building materials locally. Pottery and tiles produced in the factory during its ten years of operation are incised with “Catalina Island” or “Catalina” on the bottom and have distinctive colors such as Toyon red, Descanso green, Mandarin yellow, and others. After the factory closed, the molds were sold to Gladding McBean on the mainland. They used the Catalina name for a while and marked it with blue or black ink.

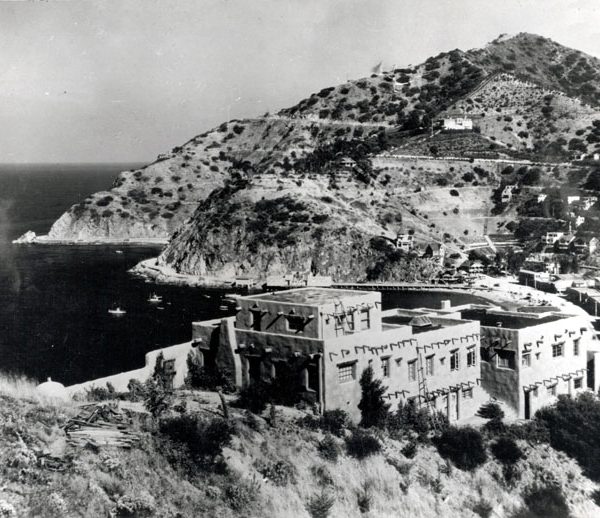

In October 1995, the University of Southern California received a grant from the Wrigley family to expand the scope of their USC Marine Science Center at Fisherman’s Cove to include environmental sciences, hence the name change. The lab was renovated in 1996 and the dorms in 1997. The hyperbaric and decompression chamber is operational for emergencies (divers with the bends). Expanded educational programming includes classes for USC and California State University students, the USC Sea Grant Program/Island Explorers which includes curriculum and an overnight visit for K-12 students, and Elderhostel. Postdoctoral fellows and other scientists are conducting ambitious new environmental research projects.

In 1542, Catalina Island was discovered by Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, who named it San Salvador and claimed the island in the name of the king of Spain. In 1602, the island was rediscovered by Spanish explorer, Viscaino, who landed here on Saint Catherine’s Feast Day (St. Catherine of Alexandria). He named it Santa Catalina Island in her honor.

The Gabrielino Indians lived on Catalina Island for over 7,000 years. When Cabrillo discovered the island in 1542, it was claimed by the king of Spain. Mexican ownership dates from 1821, when Mexico achieved its independence from Spain. In 1846, Governor Pio Pico of Mexican California granted Catalina Island to a private citizen, Tomas Robbins, who owned it until 1850. In that year, he sold Catalina to Jose Maria Covarrubias for $10,000.

Covarrubias sold the island to Albert Packard of San Francisco in 1853. The Island then went through a complex phase of ownership changes and divisions until it was acquired by James Lick in 1864. By 1867, Lick had entire ownership of the Island. In 1887, George Shatto bought the entire Island for $200,000 from the Lick Estate (Lick died in 1876), but lost the island due to debt and foreclosure.

The Lick Estate then sold the island to William Banning in 1892 for $128,740. The Bannings established the Santa Catalina Island Company in 1896 and transferred ownership of the Island to the Company that year. After a devastating fire that burned a quarter of Avalon in 1915, the Bannings faced financial difficulties and sold the Island Company to William Wrigley, Jr. of Chicago Cubs and chewing gum fame.

This now-historic event cast the die for permanently preserving substantially all of Santa Catalina Island in its natural state. During the next 56 years, various conservation practices were initiated by the Wrigley-led Santa Catalina Island Company, including much-needed animal controls, protection of watersheds and reseeding of overgrazed areas.

Throughout the term of the Wrigley family stewardship, the interest in conservation increased. In 1972, members of the Wrigley family established the Santa Catalina Island Conservancy as a nonprofit organization dedicated to the conservation and preservation of Santa Catalina Island. On February 15, 1975, the final step was taken to ensure the protection of the majority of Santa Catalina Island when Mr. and Mrs. Philip K. Wrigley and Mrs. Dorothy Wrigley Offield, through the Santa Catalina Island Company, deeded 42,135 acres of the Island to the Conservancy. With this gift, the conservation and preservation of most of Catalina’s interior and 48 miles of its coastline were given permanent status in perpetuity. Prior to this, in 1974, the Santa Catalina Island Company entered into a 50-year open space agreement with Los Angeles County, guaranteeing public recreational and educational use of 41,000 acres of Santa Catalina Island, consistent with good land conservation practices. When the Conservancy received land title to most of the Island a year later, it took over the responsibility for the County easement of 41,000 acres of the Conservancy’s 42,135 acres.

The island was formed by subduction in which the Pacific tectonic plate goes under the continental (mainland) plate.

The U.S. Maritime Services (Merchant Marines) were in Avalon, the Army Signal Corps were at Camp Cactus, the Coast Guard was at the Isthmus, and the Office of Strategic Services was at Toyon.

The four Northern Islands are San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa. The four Southern Channel Islands are San Nicolas, Santa Barbara, Santa Catalina, and San Clemente. Channel Islands National Park includes the islands of Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, and San Miguel.

Avalon is the only incorporated city on any of the Channel Islands. The Navy has small installations on San Clemente and San Nicolas Islands. There were small ranching operations on several of the Northern islands in the past (Santa Rosa still operates as a cattle ranch).

The island where the Native American woman lived alone for 18 years (after the rest of her people were taken by boat to the mainland) was San Nicolas Island. The book Island of the Blue Dolphins was written by Scott O’Dell. The true story on which he based his book tells of the “Lone Woman of San Nicolas.” Because of the island Indians’ repeated confrontations with sea otter hunters, mission padres on the mainland feared for the Indians’ safety and in 1835 sent a schooner to evacuate the island. As they were loading the ship, one woman realized her child had been left behind in the village and hurried off to find it. With strong winds rising, the ship had to sail away, leaving the woman behind. Wild dogs apparently had killed her child and the ship could not go back for her. She stayed alone on the island until a hunter, George Nidever, discovered her. He brought her home to live with him and his wife in Santa Barbara, but she died less than two months later of dysentery. (Information from Jan Timbrook, “The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island,” Bulletin of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, no. 155 (November 1991.)

Animals which are considered “native” to the Island include Catalina Island gray fox (probably brought to the Island from other Channel Islands by Native Americans), small rodents such as mice, squirrels and the ornate shrew, bats, 6 kinds of snakes including Pacific rattlesnake, lizards, and tree frogs. Animals which are considered “introduced” (newcomers) include goats (most likely introduced in the early 1800s, rather than by the Spanish explorers who came much earlier, as is commonly thought), bison (1924), mule deer and wild boar (introduced to the Island in the 1930s), black buck antelope (1972), and bull frogs. Catalina also has many species of birds including the bald eagle which has been reintroduced to the Island through the Institute for Wildlife Studies Bald Eagle Project.

Fourteen were brought to Catalina in 1924 to make a film, though presently the name of that film is unknown. Today the population is maintained at about 200. Periodically the herds are thinned out by the Santa Catalina Island Conservancy and the surplus bison are sold and shipped to the mainland.

Fenced in by ocean and free of large predators, Santa Catalina Island attracted enterprising ranchers who hoped to make money raising sheep and cattle for wool, mutton, hides, and beef. Tomas Robbins, an American who became a naturalized Mexican citizen, established the first ranch on Santa Catalina island in 1846 when he received the Island as a land grant from Mexican governor Pio Pico. Four years later, he sold the Island to Jose Maria Covarrubius, first in a series of absentee owners. Squatters soon settled in various coves that still bear their names. Most of them raised sheep, which reportedly numbered more than 20,000 by 1864. When James Lick acquired the Island in 1867, he evicted all but three of the squatters, who were granted leases to run sheep and cattle. From 1915-1923 the Mauer Cattle Company leased grazing rights from the Santa Catalina Island Company (formed in 1894). When its lease expired, the Santa Catalina Island Company took over ranching operations, maintaining several thousand head of cattle until the 1950s. Today, no sheep or cattle remain on the Island.

In 1887, George Shatto, a 37-year-old Michigan businessman, bought Catalina Island with the intent to create a winter resort. He immediately began making plans to build a town (which became Avalon), initiated the construction of the Hotel Metropole and a wharf, and placed into service his steamer, the Ferndale

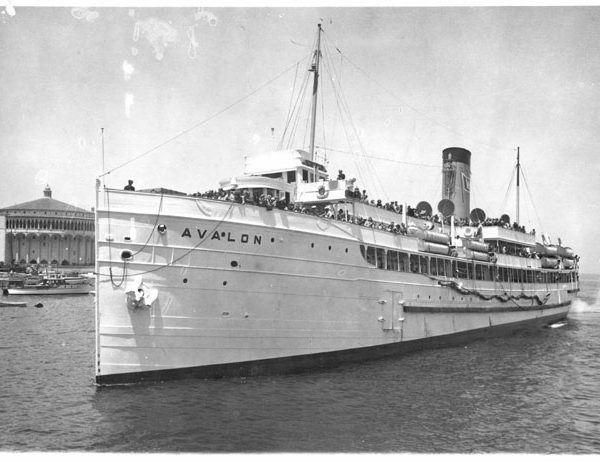

Phineas Banning, a prominent stage coach line operator based in the Los Angeles area, began operating a regular steamship between the Island and the mainland in the mid 1800s. By the early 1880s, the Banning family saw another opportunity as the Island started to attract visitors and residents. In 1884, they established the Wilmington Transportation Company, which oversaw a series of ships making the run to the Island. When George Shatto ran into financial troubles, the Bannings purchased the Island from him in 1892, increased their fleet of ships, and spurred on the Island’s fledgling tourist industry.

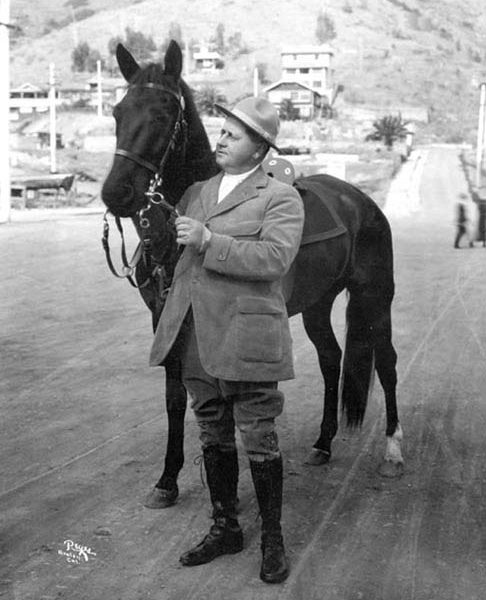

The Bannings built the island’s first substantial infrastructure, providing water, electricity, waste disposal, and communications services, building good roads, and installing law enforcement and fire protection services. During the period they owned the island, from 1892 to 1919, visitor attractions on the Island also expanded exponentially to include a dance pavilion, golf course, tennis courts, an incline railway, Greek amphitheater, and aquarium. Tourists could enjoy the music of the Porters Catalina Island Marine Band, hunt and fish, watch fireworks, take stagecoach rides, and view the wonders of the sea through the floors of glass-bottomed boats. George S. Patton, Jr., destined to become famous as a general during World War II, spent his summers at a family home on the Island during this time.

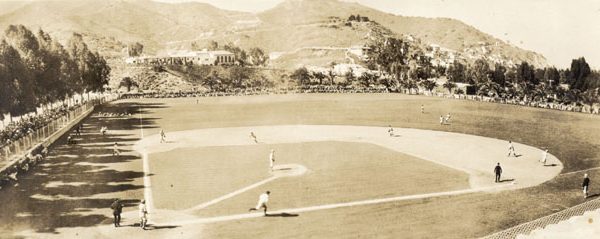

The Wrigleys of Chicago purchased Catalina Island in 1919 and quickly set about developing it further. With William Wrigley, Jr., guiding its evolution, the Island was soon home to the Sugar Loaf Casino, Atwater Hotel, Band Box Theater, Bird Park, and Catalina Clay Products plant. The Wrigleys imported deer and boar for hunters, brought in the Chicago Cubs for spring training, and began hosting the Bobby Jones Amateur Golf Tournament. To get to the tourist paradise, visitors could steam to the Island in the expensive and spacious SS Avalon and SS Catalina or take advantage of the new cross-channel air service.

After Catalina Island was sold to George Shatto in 1887, he had the town surveyed and streets laid out. He then sold the first lots. He didn’t want the town named “Shattoville” and asked his sister-in-law, Etta Whitney, to name the town. She chose “Avalon,” a Celtic word meaning “island of apples.” It is also the name of the place in Tennyson’s poem, “Idylls of a King,” where King Arthur went to heal himself.

Lookout Cot (later Holly Hill House) was built in 1890 as a private residence by Peter Gano, a retired engineer from Pasadena. His sister was to come live with him, but she never did. He did allow women on the property.

The Chicago Cubs had spring training nearly every year from 1921 to 1951 at the Las Casitas ball field on Avalon Canyon Road. There is a memorial plaque on the site.

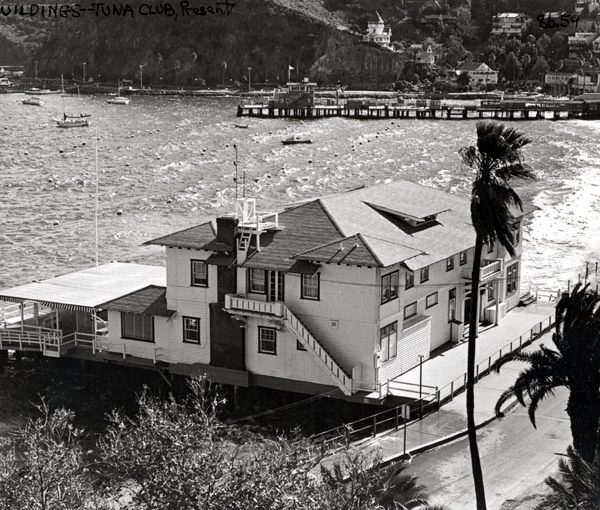

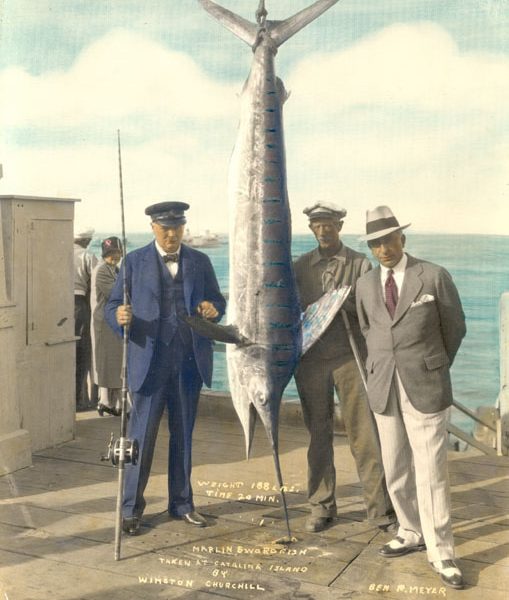

The Tuna Club was founded in 1898, by Charles Frederick Holder. Holder and the Tuna Club pioneered and popularized sportfishing as a conservation measure to slow down the declining numbers of fish. The goal was to give the fish a fighting chance by using the lightest weight fishing line possible. It is an exclusive club and membership is partially based on the ability to capture certain species of fish using specified weights of fishing line.

The Catalina Island Museum at 1 Casino Way in Avalon (310/510-2414) has original photographs.