San Dimas

Community History

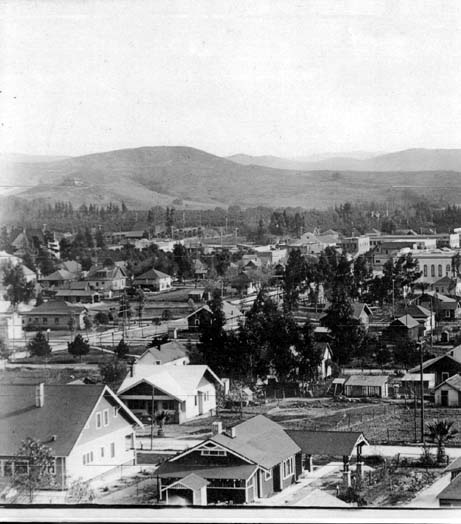

San Dimas, a city of about 35,000 people, is located approximately thirty miles east of downtown Los Angeles, in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains and straddling the San Gabriel and Pomona valleys. The community started out in the early 1800s being called Mud Springs, named for the adjacent Mud Springs marsh whose wet and swampy terrain characterized the region. Though Gabrielino Indians occupied the area as early as 1000 B.C. and other tribes as much as 7,000 years ago, it was not until 1774 that white men first ventured into the region, when Spanish frontier soldier Juan Baptista DeAnza and his party, en route from Mexico to Monterey, passed through the area that later became Mud Springs.

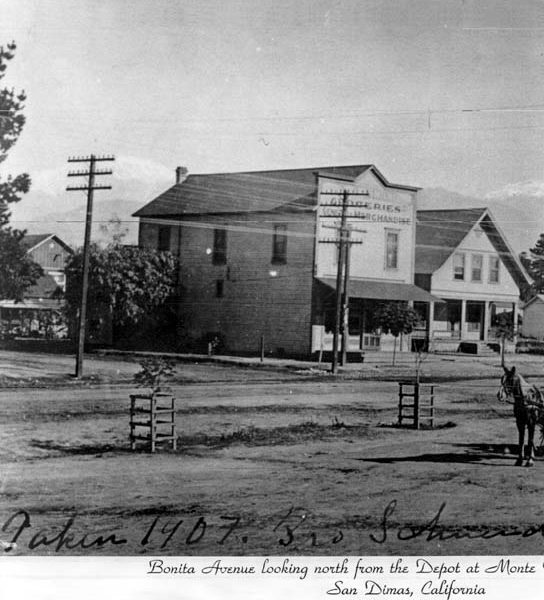

Other explorers, early settlers and cattle ranchers trickled into the region in the century that followed, but the community was formally put on the map in 1887, the year the Santa Fe Railroad was completed and began operating a rail line through the area. The railroad’s arrival triggered a land boom. The newly formed San Jose Ranch Company laid out streets and lots, land agent E.M. Marshall opened the first business, a hardware store, at the corner of Bonita and Depot streets and the name Mud Springs was changed to San Dimas.

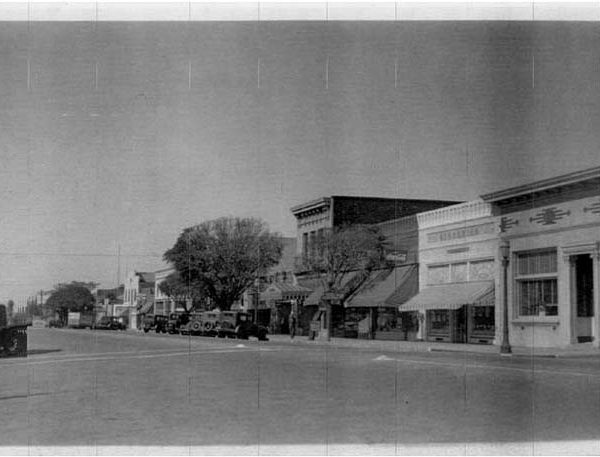

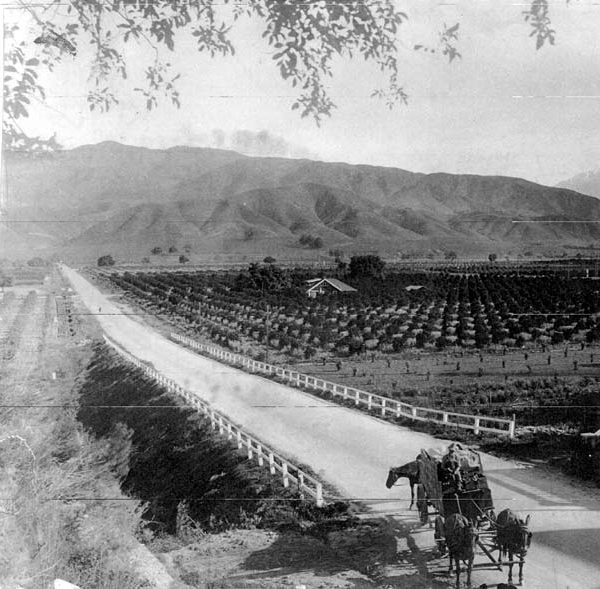

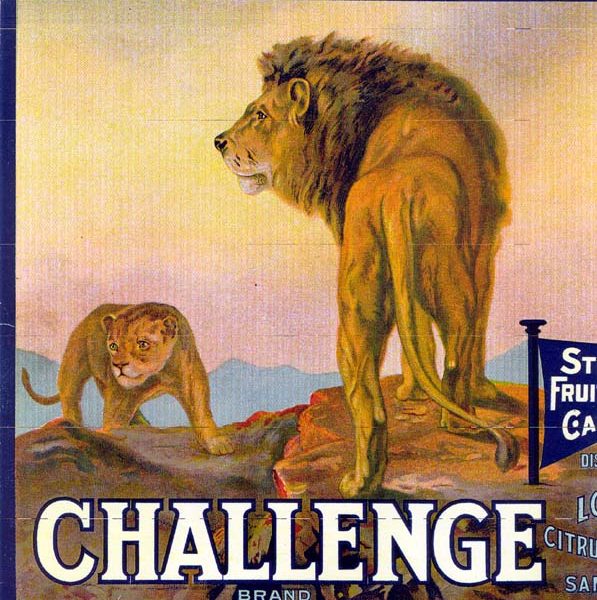

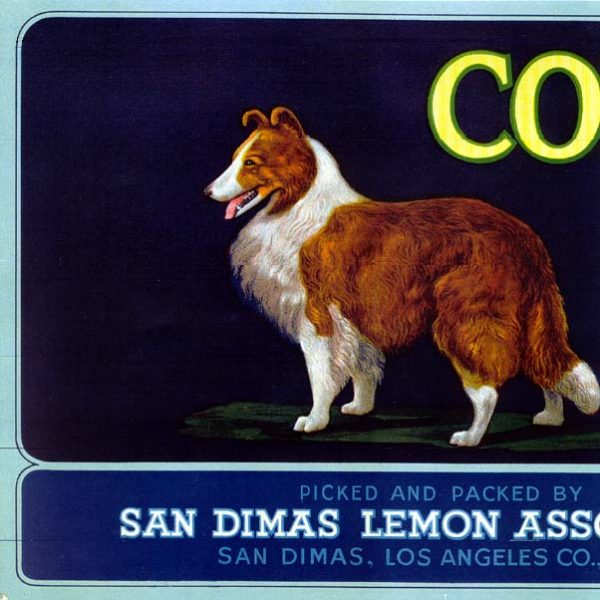

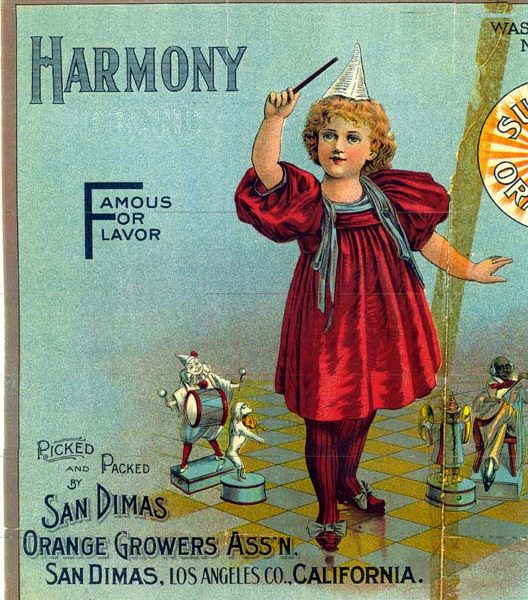

San Dimas evolved into an agricultural community, especially noted for its orange and other citrus crops which were shipped all over the world. The citrus nurseries faded and finally disappeared in the mid-1900s with increasing development in San Dimas. After adjacent communities started annexing pieces of San Dimas in the late 1950s, it incorporated as a city in 1960. Today, conscious of its heritage, San Dimas maintains an early western look in its downtown area, complete with wooden sidewalks and old-fashioned western storefront facades.

Frequently Asked Questions

The early settlement that preceded San Dimas was called Mud Springs and, briefly, Mound City. According to local legend, Don Ygnacio Palomares, who received the Rancho San José as part of a Mexican land grant, kept some of his cattle in a corral in the so-called Horsethief Canyon. After Native Americans repeatedly ran his horses off, he prayed to St. Dimas, the crucified thief who begged forgiveness for his sins and later became patron saint of thieves. Soon the canyon in question was renamed San Dimas Canyon by Spanish settlers, and when the town was laid out in 1887, founders appropriated the name, which sounded better than “Mud Springs” and would therefore be more likely to attract new residents.

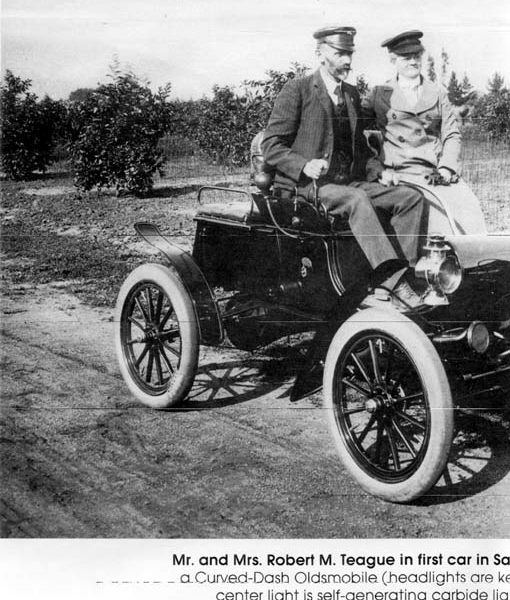

As long ago as 1000 B.C., Gabrielino Indians were thought to be the first inhabitants of the region that became San Dimas, though some archaeologists have found evidence that other Indians tribes lived there 7,000 years ago. Spanish frontier soldier Juan Baptista DeAnza and his party were the first white people to pass through the area when, in 1774, they stopped in what later became Mud Springs en route from Mexico to Monterey. More than half a century later, Jedediah Strong Smith was the first American to come overland when he camped in the region on a beaver-trapping expedition. Inhabitants started putting down roots there little more than a decade later when, in 1837, Ygnacio Palomares and Ricardo Vejar started the Rancho San Jose as part of a Mexican land grant. Between 1872 and 1870 Dennis Clancy and his wife ran a stage station near Mud Springs and their children were the first Americans born there after California joined the Union in 1850. The Teague family, whose citrus nurseries would become world-famous, arrived in 1878 and planted their first citrus trees the following year.

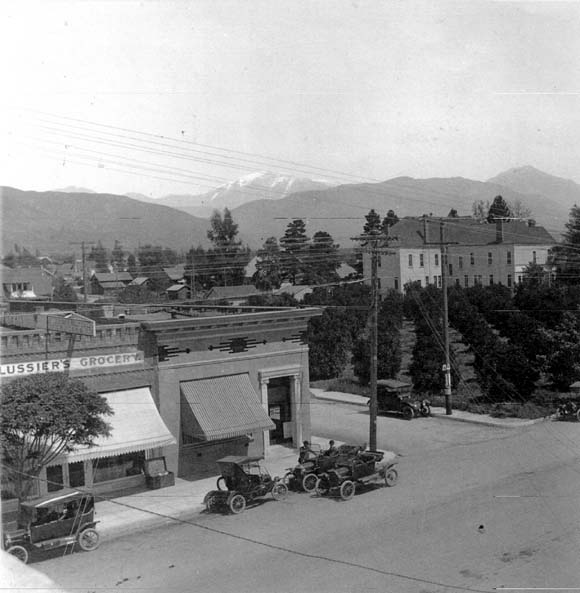

The town of San Dimas began in 1887, a product of Southern California’s great land boom. This boom was one of four such bursts of population and development in the southern part of the state in the half century between 1876 and 1923. Among the major reasons for the land boom was completion of a transcontinental railroad as well as more localized rail expansion. For San Dimas, the catalyst for development in 1887 was completion of the Santa Fe Railway’s main line through the area. In short order, the San Jose Ranch Company was created and began to lay out plots of land and streets in the town. More development followed in a fast domino effect, and by 1890 San Dimas had a planing mill, a hardware store, and fourth-class post office at the corner of Bonita and Depot, a brick kiln at the corner of Amelia and Cienega, two pipe yards, and its first telephone and restaurant. The community grew as an agricultural region, though its crops gave way to houses and other development by the middle part of the 1900s.

As early as 1912 the Board of Trade talked about incorporating as a city, but following a year of discussion and dissension they dropped the idea. Residents’ desire to incorporate came back in the late 1950s, after adjacent communities began encroaching on San Dimas through annexation. On June 28, 1960, San Dimas voters cast a majority of ballots to incorporate as a city, a decision that became official on August 4, 1960. San Dimas became the 70th city in Los Angeles County.

Cattle ranching was the primary occupation in Southern California between 1820 and 1860, and the area around the community that became San Dimas had its share of ranches as well. Best known, perhaps, is the Rancho San José, given in a Mexican land grant in 1837 to Don Ygnacio Palomares and Ricardo Vejar. However, “Bob” Teague started what would become the world’s largest citrus nursery in its day when in 1889 he plantedon one acre10,000 orange, lemon, and grapefruit trees. By 1900 he had by some reports as many as 700,000 seedlings, and during the peak years between around 1910 and 1912, his annual sales reached $100,000.

By the first two decades of the twentieth century, citrus plantings dominated the valley. San Dimas was an especially good place to grow lemons because of its elevation in the foothills of the San Gabriel mountains. Until the winter of 1913, even frost was not a problem. Growing citrus could be risky, since growers had to combat theft of fruit and cope with blights and frost. However, as the twentieth century progressed, citrus no longer reigned in San Dimas due to the so-called “quick decline disease” and a growing number of subdivisions and freeways. In 1963 the last packing house closed and in recent years the last grove was plowed under for development.